By Athena Smith

October 15, 2025

Introduction

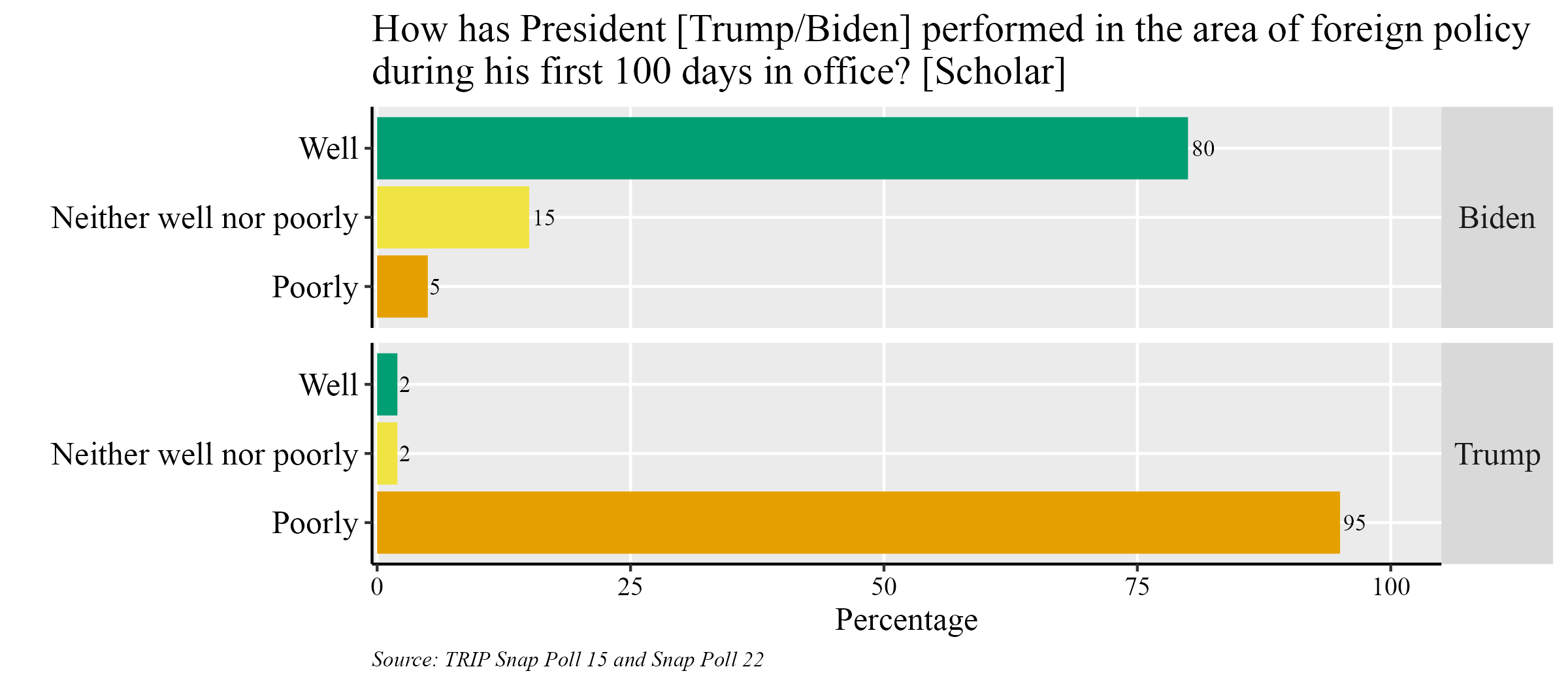

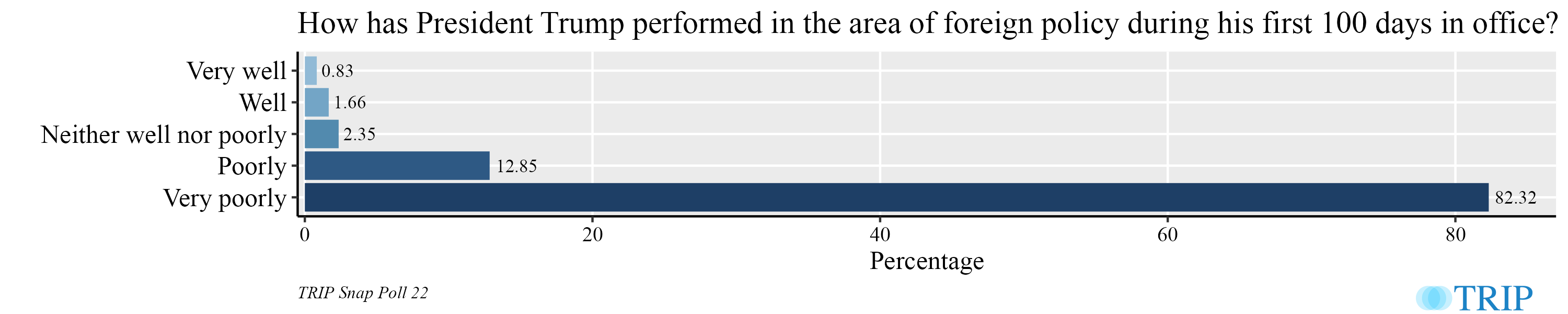

Scholars of international organizations overwhelmingly evaluated President Trump’s foreign policy within his first 100 days as negative, and they did so at consistently higher rates than the broader community of international relations scholars. These findings suggest experts viewed Trump’s early actions as damaging to the international order. The international order often hinges on support for institutions’ rules and cooperative frameworks; for example, withdrawals from agreements such as the Paris Climate Accord or threats to NATO’s defense commitments can erode these rules.

Using TRIP’s data from Snap Poll XXII, this post compares those evaluations across paradigms and between International Organization (IO) scholars and the broader IR community to show how theoretical orientation and specialization shaped assessments of President Trump’s foreign policy in his first 100 days. In President Trump’s first 100 days, he withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement and the World Health Organization. He also shut down the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and retreated from engagement with numerous United Nations bodies.

Current practice

One of President Trump’s first executive orders, signed February 4th, 2025, is titled: “Withdrawing the United States From and Ending Funding to Certain United Nations Organizations and Reviewing United States Support to All International Organizations.” This order targets the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). President Trump argued that these institutions “act[ed] contrary to the interests of the United States,” “propagat[ed] anti-Semitism,” and “demonstrat[ed] anti-Israel sentiment.” He also sanctioned the International Criminal Court, primarily due to its investigations of Israeli officials.

As part of this executive order, within 180 days the Secretary of State was to review all intergovernmental organizations the United States is a member of to find if they conflict with the interests of the United States. This review would determine if the United States should withdraw its support. President Trump’s cancellation of billions of dollars in U.S. foreign assistance, along with his administration’s efforts to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), represent a significant reduction in American commitments abroad. Similarly, his targeting of the UN Human Rights Council and other international agencies reflects a broader effort to weaken international institutions and reduce U.S. engagement abroad.

Data and Analysis

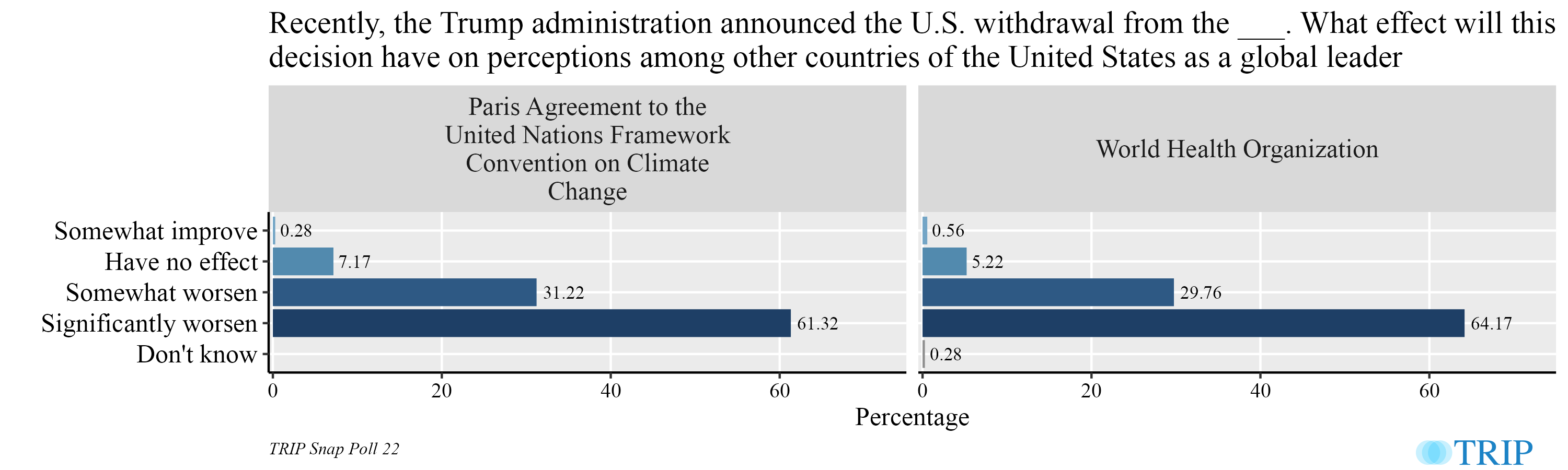

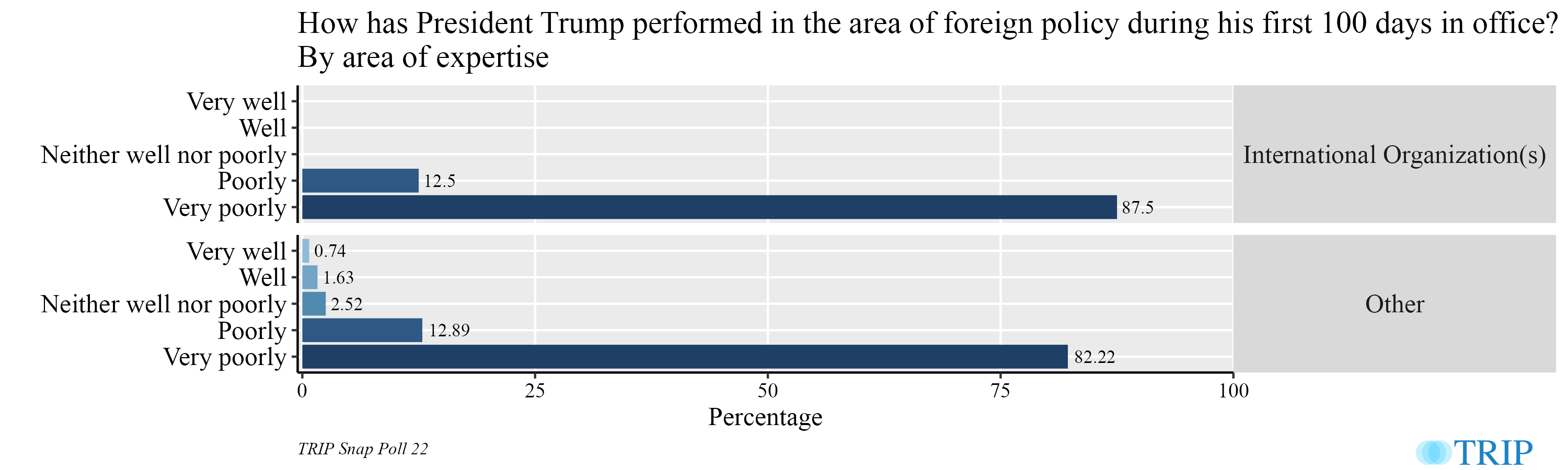

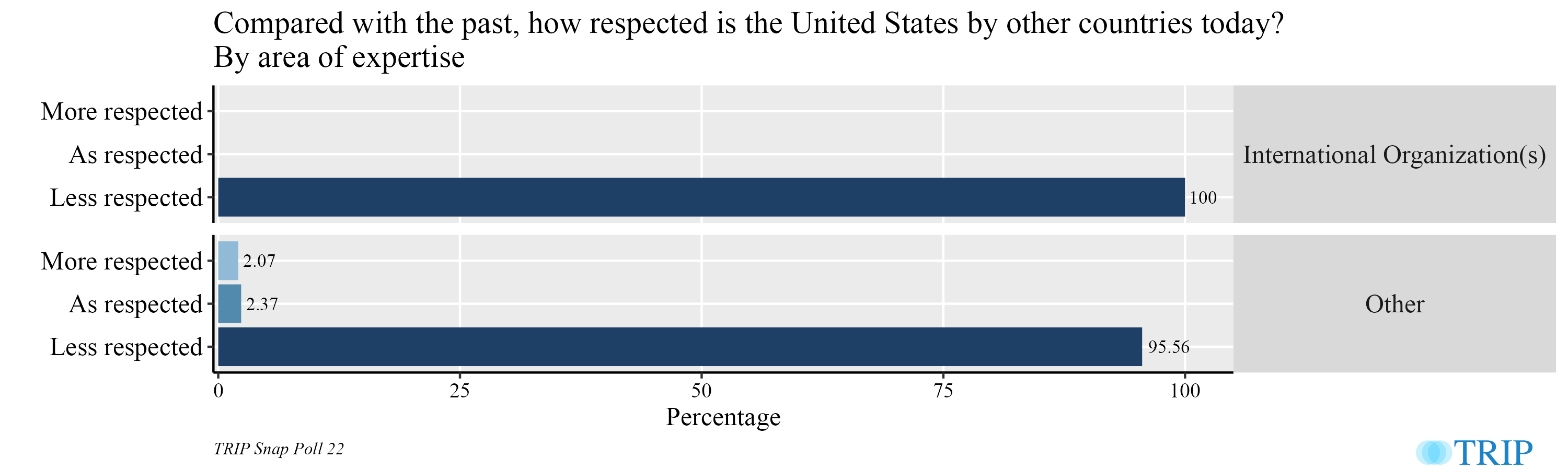

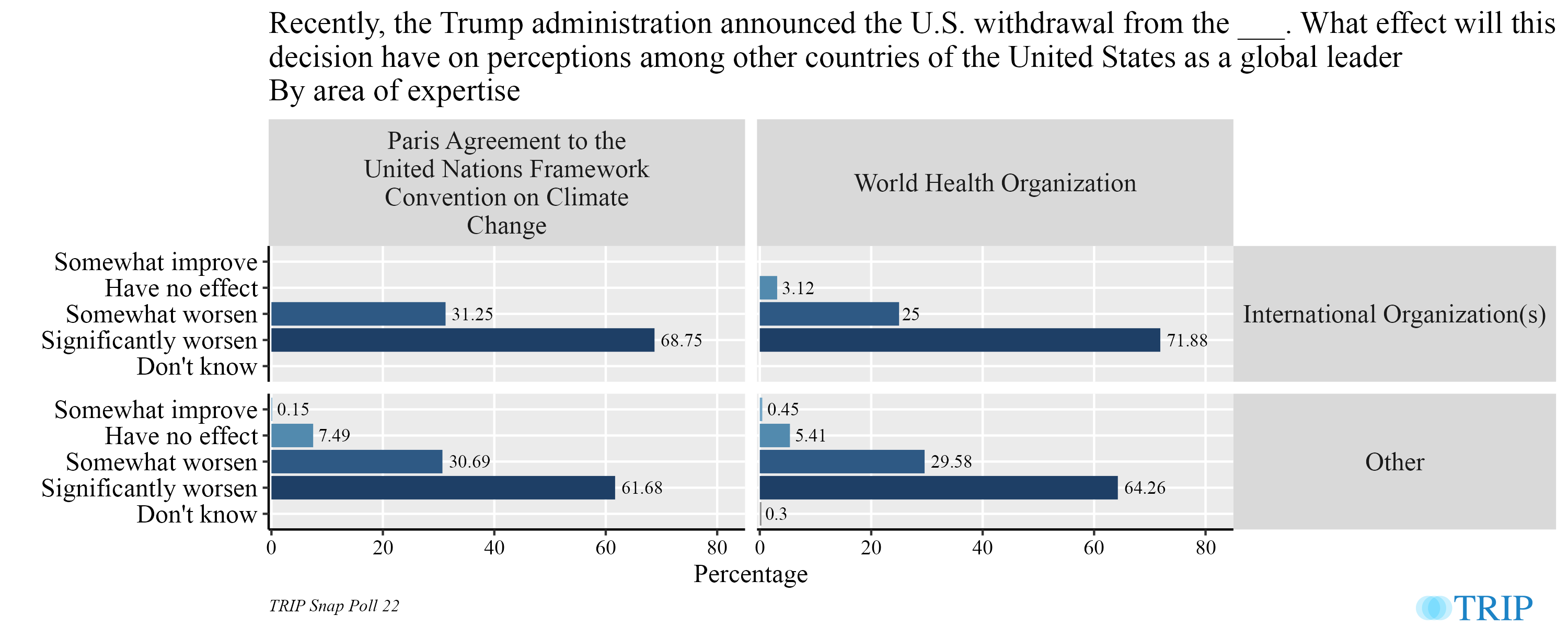

On the question of how President Trump has performed in the area of foreign policy during his first 100 days in office, 82.3% of scholars rated the president “very poorly.” Additionally, 95.7% of scholars said that compared with the past, the United States is less respected by other countries today. Sixty-one percent of scholars said President Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change would significantly worsen perceptions among other countries of the United States as a global leader, and 64% of scholars said the same of President Trump’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization. Higher disapproval rates suggest a deeper understanding of the dangers of eroding norm-based institutions such as international organizations, which do not have a basis in binding law and rely on the willful participation and support of their member states.

The paradigms of international organizations scholars further impact these evaluations, as realism, constructivism, and liberalism hold varying perspectives on the behaviors of states in the international system and subsequently, on the saliency and importance of international organizations.

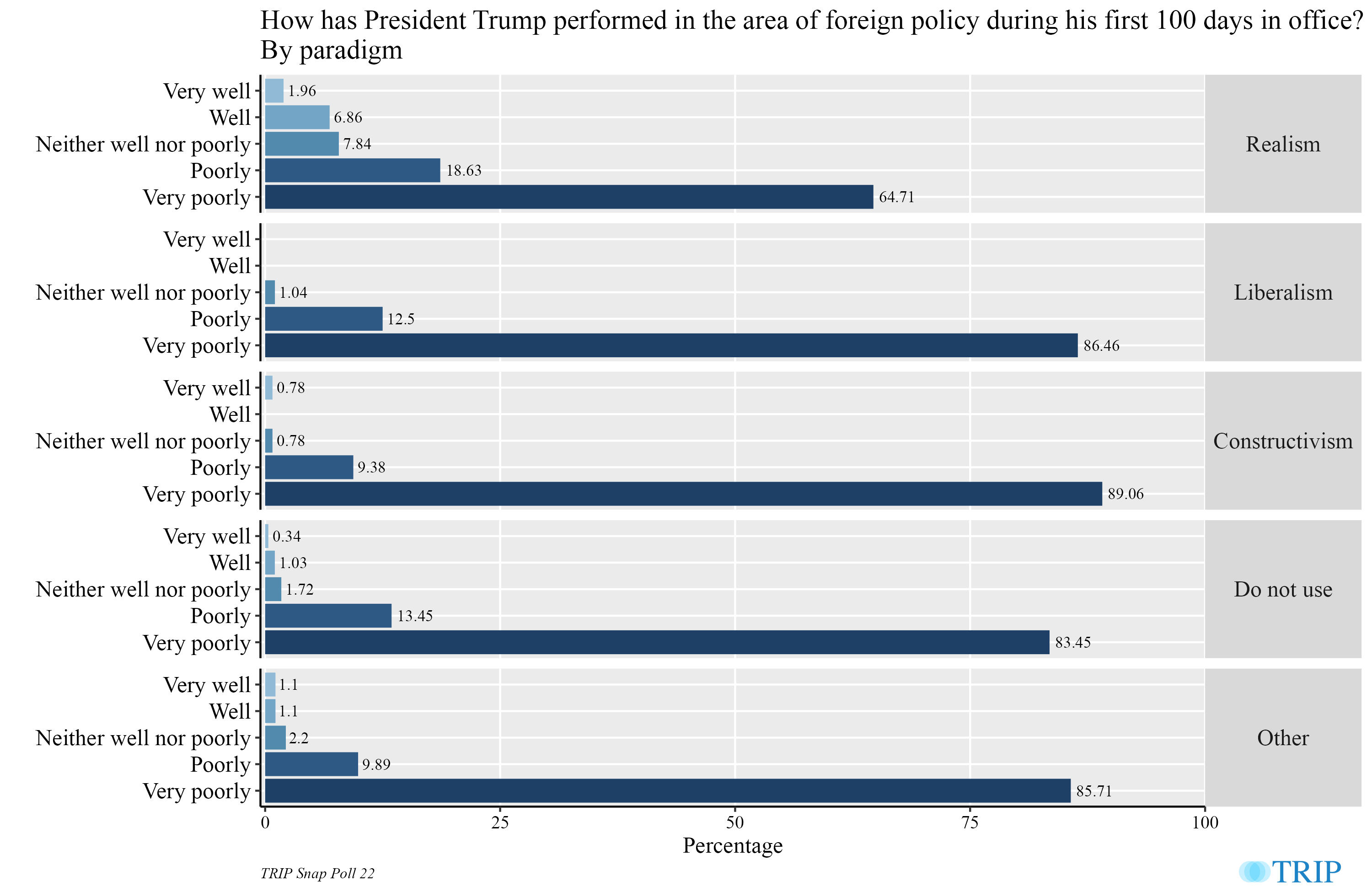

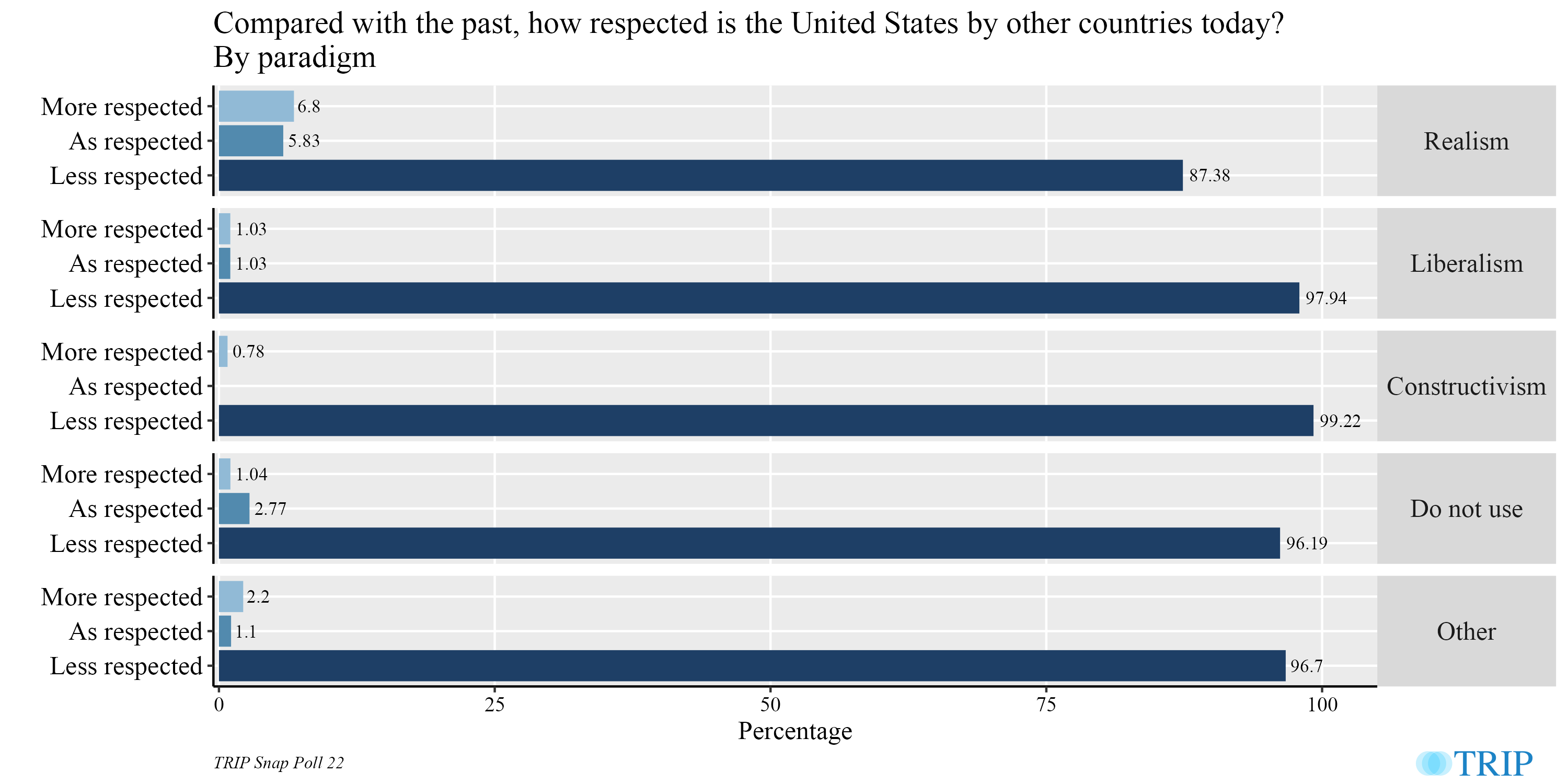

On the question of how President Trump has performed on foreign policy in his first 100 days in office, realists evaluated his performance “very poorly” at 64.7%, whereas liberals responded “very poorly” at 86.46%, constructivist 89%, and those who did not use a paradigm at 83.5%. On America’s respect in the world, 87.4% of realists said America was less respected today, compared with 97.9% of liberals, 99.2% of constructivists, and 96.2% of those who do not use a paradigm.

Individual paradigms reflect personal perspectives on the significance of President Trump’s policies for the international order; scholars who believe states are self-interested and competitive saw President Trump’s policies more positively compared to scholars who believe norms and institutions are more salient in our international system. Liberals and constructivists believe in the importance of international organizations and the saliency of norms and institutions which shape state power. Realists, on the other hand, believe that national interests and power determine behaviors; this leaves them more skeptical about liberal internationalism.

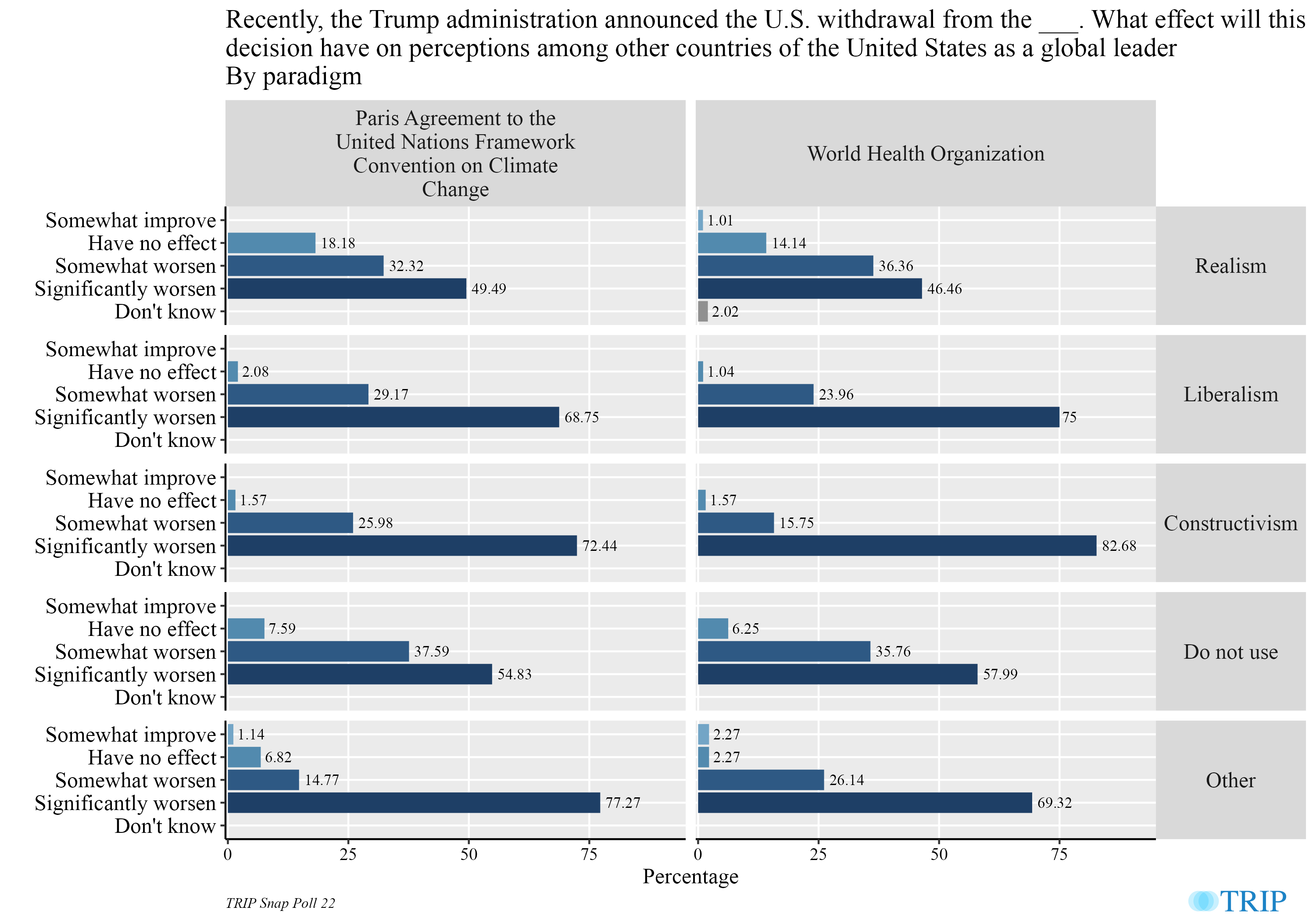

The same trend is reflected across the last two questions; forty-nine percent of realists believe President Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement will significantly worsen global perceptions of America. This stands in comparison to 68.7% of liberals, 72.4% of constructivists, and 54.8% who do not use a paradigm. Forty-six percent of realists believed the same about Trump’s WHO withdrawal, compared to 75% of liberals, 82.7% of constructivists, and 58% of those who do not use a paradigm.

Disapproval is heightened across these same four questions for scholars of international organizations. This reflects the concern that President Trump’s skepticism of international norms presents a structural challenge to the legitimacy and stability of the international institutional system. On the question of how President Trump has performed on foreign policy in his first 100 days in office, scholars of international organizations rated his performance as “very poorly” at 87.5%, compared to 82.2% of all other scholars. One hundred percent of these scholars agree that other countries now respect the United States less than in the past, compared to 95.6% of other scholars.

IO scholars also evaluated President Trump’s stance on the Paris Climate agreement more harshly; sixty-eight percent said the withdrawal would significantly worsen American perceptions abroad, and 71.9% of IO scholars said the same of President Trump’s withdrawal from the WHO. These results suggest that both paradigm and specialization strongly color scholars’ perceptions of President Trump’s foreign policies in his first 100 days. Additionally, the data show that IO scholars and non-realist paradigms converge on the view that these policies had disproportionately negative implications for the institutional order.

Conclusion & future implications

Concerned evaluations from IR scholars reflect the reality that the role of the United States in the international order has shifted in President Trump’s first 100 days, as his “America First” program questions and weakens international norms and processes. President Trump’s recent executive orders reflect the belief that the United States is afraid of international cooperation undermining national sovereignty and perceived interests.

A fragmented American approach to international norms will make it more difficult for other states to maintain their commitments to existing standards and solve global challenges. Eroding consensus also means that big issues, like climate change and refugees, will not be met with effective responses at the global level. Buy-in from states is necessary in order to properly condemn bad behavior, and a decline in adherence to norms can also raise the possibility of miscalculation and conflict. President Trump’s early foreign policy decisions raise critical questions about the resilience of global cooperation.