By Morgan Doll

July 17, 2020

Edward Mansfield and Jon Pevehouse in “Trade Policy and Trade Policy Research” and Robert Zoellick in “Making International Relations Research On Trade More Relevant to Policy Officials” address the policy-scholarship divide in International Political Economy. Of articles that analyze trade in leading IR journals, “only 5 percent are coded as making an explicit policy recommendation.” While 52 percent of policymakers responding to the 2017 TRIP trade policy maker survey “reported relating arguments and evidence from social science research into their work on a daily basis,” it is impossible to tell whether specific policy recommendations by scholars have had an impact on policy decisions in practice. Mansfield and Pevehouse find, instead, that “developments in the global arena—many of which are driven by policy initiatives—are an impetus for much of the academic literature on the political economy of trade.” Zoellick in his response agrees with Mansfield & Pevehouse on the importance of history. He makes an addendum, emphasizing how transformative leaders play a role in this discussion. He points out how there are “times when political leaders resist and even block structures or systems that they believe are counterproductive” and, “in doing so, transformative leaders can create the basis for new, or at least substantially revised, orders.” In his opinion, both governments and citizens could gain a lot from scholarly contributions in policymaking.

In the current era of President Donald Trump, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and widespread anti-globalization sentiment, it is undeniable that the status quo has changed. With the Trump presidency, it seems as though policymakers are engaging even less with scholars. For example, in Snap Poll X, we asked scholars if they thought that free trade agreements between the U.S. and other countries have been a good thing or a bad thing for the United States. An overwhelming majority, 94.57% of respondents said that they have been a good thing.

In spite of this information, Donald Trump and his advisors have increased trade protections on U.S. goods and started a trade war with China. During the COVID-19 pandemic, President Trump has withdrawn from the WHO and pressured states to re-open despite public health officials’ advice, ignoring scholarly opinion once again. However, scholars are seemingly engaging more with policymakers today by critiquing and weighing in on the current President’s decisions. When searching for scholarly articles about “Trump” and “Trade” from 2016-2020 in the SWEM Library Database, 348,135 results came up. In comparison, when searching for “Obama” and “Trade,” 322,582 results surfaced, a 25,553 article difference. TRIP Snap Poll XI, which was released in 2018, shows that 64.64% of scholars report engaging in policy advocacy at the very least occasionally. That being said, there is no information on whether or not these scholars make explicit policy recommendations in their work, or what types of advocacy these scholars engage in.

Zoellick’s statement about political leaders creating a revised order by blocking systems they personally believe are counterproductive is precisely what President Trump has done during his term. The Trump Presidency has defied many norms, altering perceptions of the American presidency forever. This president does what he and his political base want, without considering the consequences, on issues from trade to education and public health. A new development that we must grapple with is the fact practitioners in the sphere of international relations are not always rational actors.

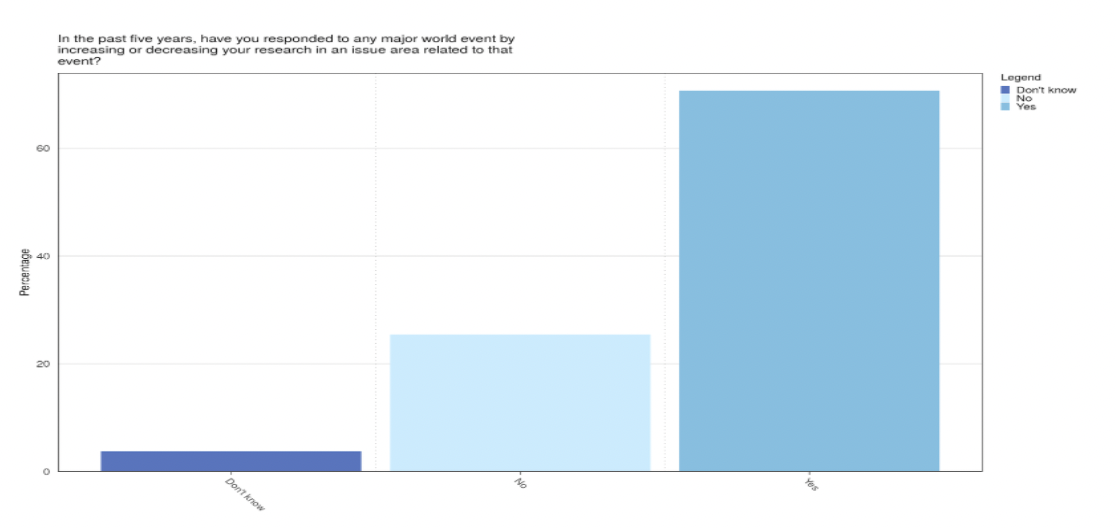

In agreement with Mansfield and Pevehouse’s view that developments in the global arena often affect scholarship, the COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged scholars to question and research more about globalization, climate change, and global health. In Snap Poll XIII, 30.33% of respondents anticipated changing the focus of their research in response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Additionally, in the 2017 TRIP Faculty Survey, 70.73% of respondents reported responding to any major world event in the last five years by increasing or decreasing their research in an issue area related to that event.

The arguments made about trade scholarship and policymaking in chapters 8 and 9 are just as applicable to the present day. Even though these authors could not predict the future with the volatile actions of the Trump Presidency and COVID-19 Pandemic, these developments give even more context and support to their arguments about trade policymaking and scholarship.

Preview or buy Bridging the Theory-Practice Divide in International Relations from Georgetown University Press here: bit.ly/Bridging-GUP