By Maggie Manson

July 24, 2020

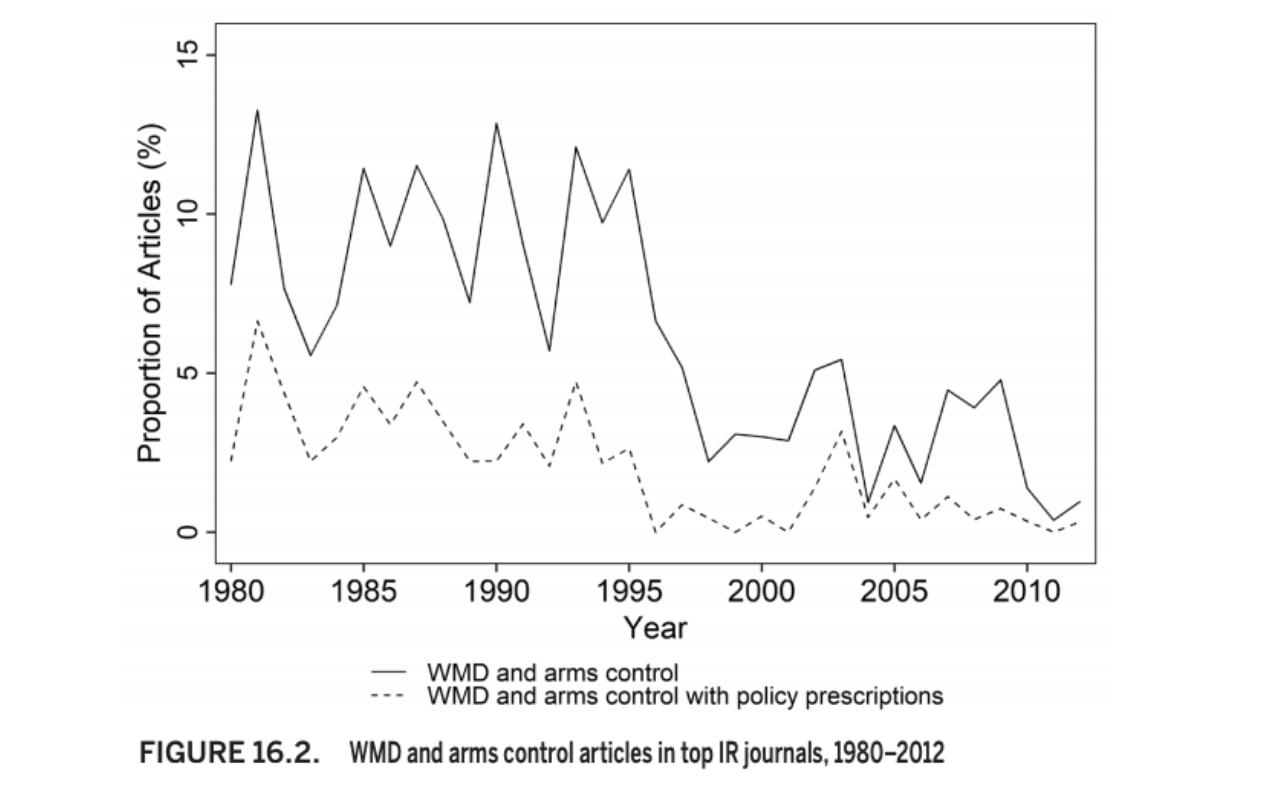

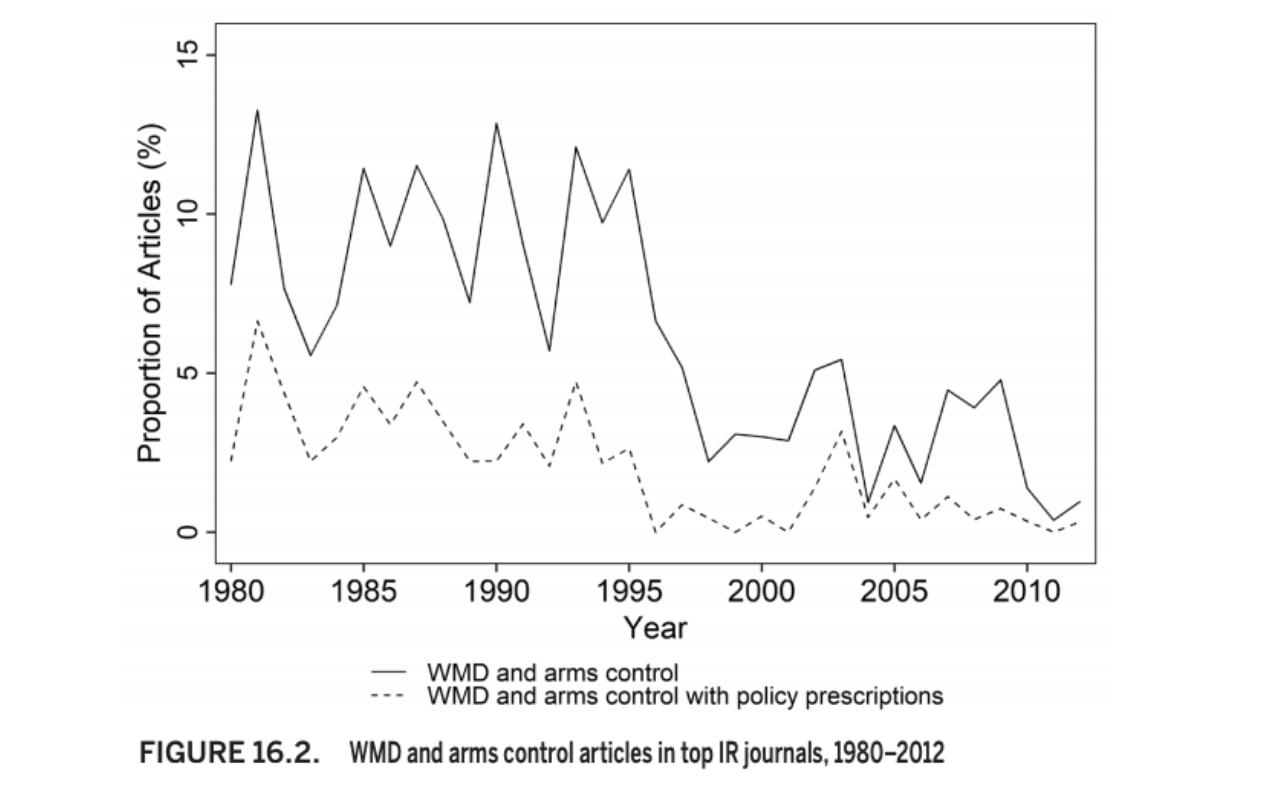

In their chapter in the new book edited by our TRIP Principal Investigators (Susan Peterson, Ryan Powers, and Michael J. Tierney) and Daniel Maliniak, Paul C. Avey and Michael C. Desch aim to solve the question of why the discipline of international security, specifically nuclear strategy, has become less policy-relevant following the Cold War. They argue that a decline in policy-relevant academia, evidenced by the decline in the proportion of journal articles with policy prescriptions, can be attributed to modern research being presented in formats that are not easily accessible for policymakers to interpret and use.

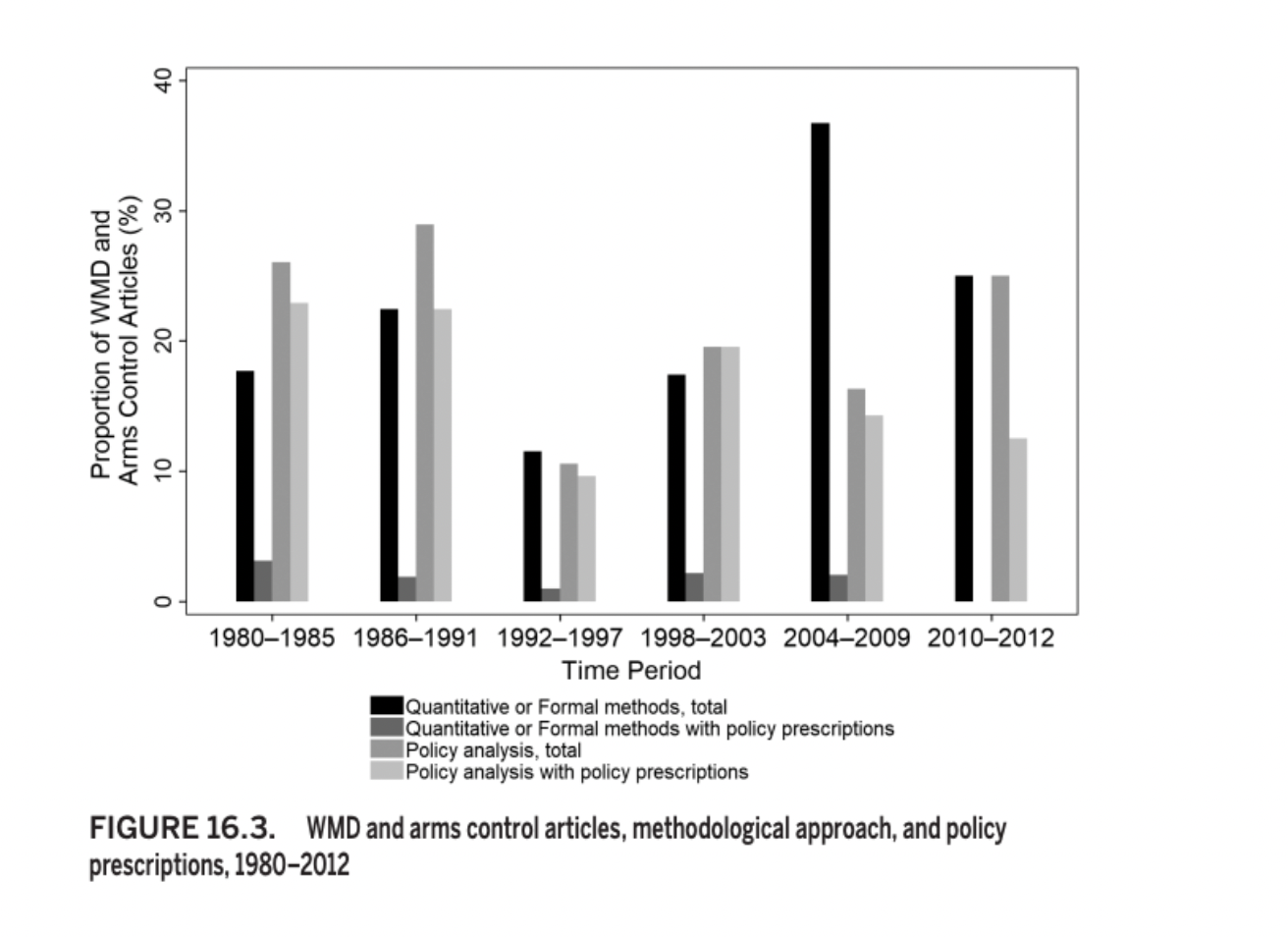

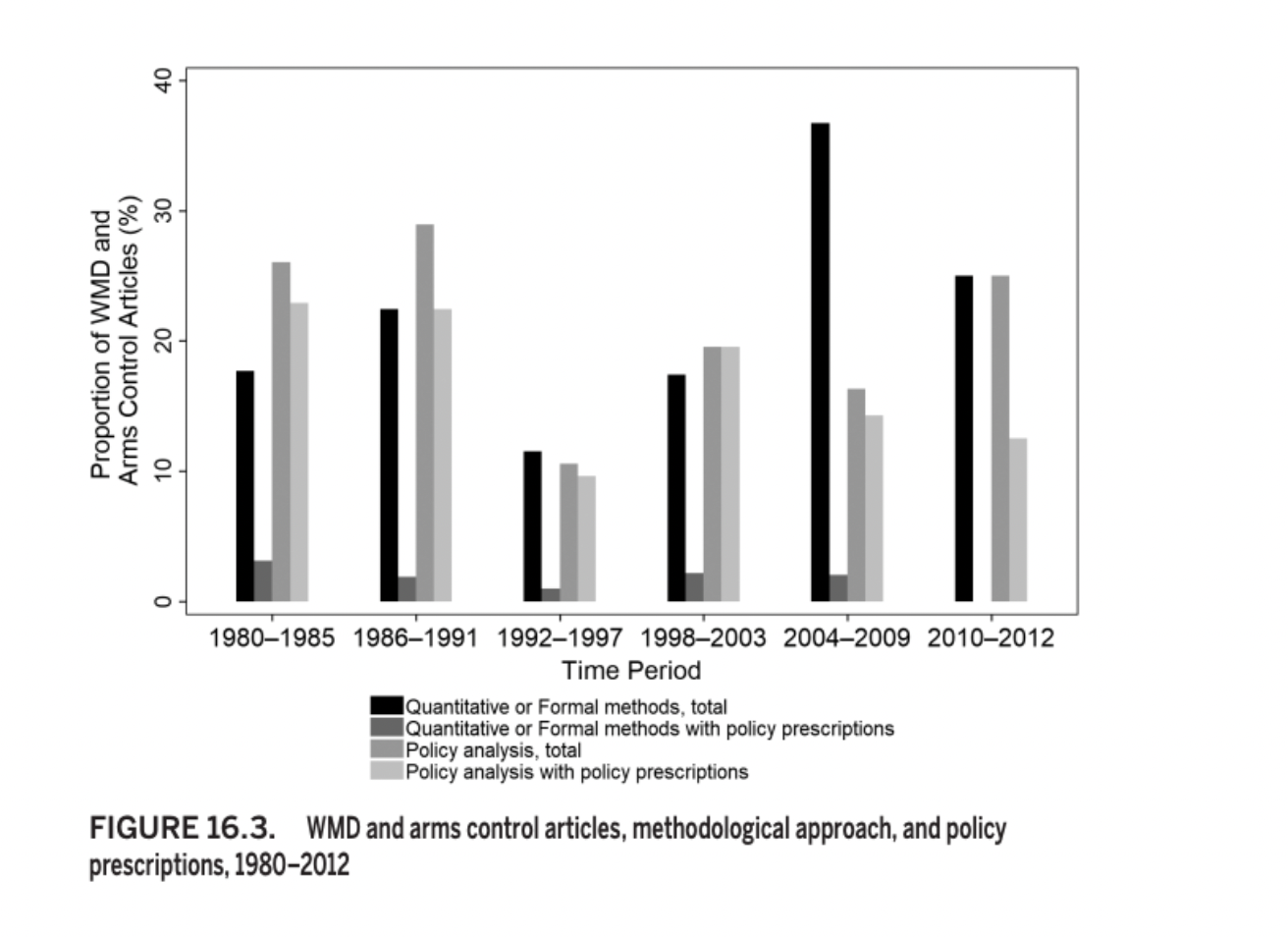

The authors find an increase in the proportion of WMD and Arms Control articles that employ quantitative analysis, rather than qualitative, which they argue is indicative of the lack of accessibility of recent nuclear research and the professionalization of IR as a field.

While the results of this chapter are interesting, I have some further questions about the applicability of these findings to the reality of nuclear politics in the Trump era. Generally speaking, nuclear research doesn’t lend itself towards quantitative methods because there is a significant lack of case studies where nuclear weapons were employed offensively (there’s exactly one, the U.S. use of nuclear weapons against Japan near the end of WWII). While aspects of nuclear politics such as hedging, proliferation, and the nonproliferation regime can be understood through quantitative analysis of real-world events, the ultimate puzzle of what factors might lead to the use of nuclear weapons cannot be solved using quantitative methods.

While the argument of the chapter may have held up in previous post-Cold War years, I believe that there is a different reason for a lack of policy relevance in the era of the Trump Presidency. The authors argue that academic work doesn’t make its way into the policy process because of inaccessible methods, however, in the case of the Trump administration, it seems that his staff often purposefully ignores expert opinion. Trump has stated many times throughout his campaign and presidency that we as a country need to be more unpredictable in our actions on the world stage. Unpredictable actions cannot coexist with well-informed policy rooted in academic findings, especially in the realm of nuclear politics. So in the Trump era, it may not in fact be that research is not well understood by policymakers, but that it is altogether ignored.

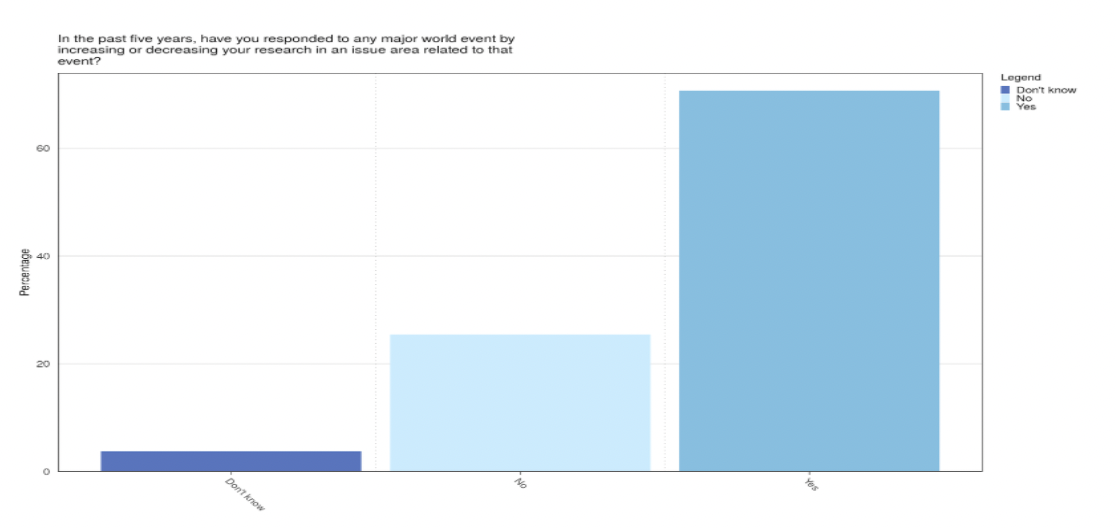

According to Snap Poll XI, a majority of scholars find Trump’s strategy of unpredictability to be highly ineffective. So why does Trump insist upon this tactic, ignoring expert opinion?

I believe that it is not because of the inaccessibility of academic work, but instead his lack of respect for expert opinion. Avey and Desch’s argument may correctly explain the theory-policy gap in the nuclear realm pre-Trump, but I think that there is a more important factor preventing the current administration from engaging with academic material: their lack of appreciation for experts altogether. This chapter and argument are extremely compelling, so I asked the authors how they think it holds up in the Trump era.

- How do you think your argument holds up in the Trump Era?

We think that the argument holds up reasonably well. If professional incentives lead nuclear scholars to turn inward to only study narrow questions amenable to certain techniques or theoretical approaches, then much of what we as scholars produce won’t be particularly relevant. There’s a lot of important questions today – from arms control to nonproliferation, to nuclear force modernization and strategy – that scholars can contribute to. It is important to put the problem at the center of analysis and then use the best approach available to answer the question. Policy practitioners are smart and can understand sophisticated approaches. But if the question and approach are not relevant to their problem set they’ll be even less likely to engage with academics. It is also incumbent on us to identify factors that policy can influence and present findings in a clear and consistent manner.

Different administrations will vary in how much they use social science work and approach experts. At its most senior levels, the Trump administration may be particularly skeptical as you note. Scholarship that is relevant may struggle to have influence across multiple administrations. The important point for us is that if the work is not relevant then there is almost no chance that it has influence.

- What are your thoughts on John Harvey’s policy response to your chapter?

We thank Dr. Harvey for taking the time to engage our argument. We agree with much of what he said, not least because he notes that our assessment is “on the mark.” His response, as he notes, reinforces and extends our points. For example, he tells the story of how Ted Postol and Sally Ride failed to achieve faculty status at Stanford. For Harvey, the problem was that “they were not doing the traditional business of academia (i.e., abstract knowledge production advancing a narrow field of study); they were working on real-world problems.” He later adds that “it was not easy to convince young social scientists and regional specialists to devote a portion of their time to policy-relevant research when prospective [academic] employers looked down on it.” Harvey highlights how disciplinary boundaries and approaches can inhibit engaging practical issues. This gets to the heart of our concern about disciplinary incentives marginalizing policy-relevant scholarship. We hope that this is changing in our field today, but we see reasons for concern. We also agree with his emphasis on time: policymakers have little of it and it matters when you introduce an idea. Scholars must be attentive to both of these factors if they work to engage practitioners.

- How does your argument fit into the limits of nuclear politics research?

There are several challenges to nuclear politics research. To highlight just two, you rightly raise the challenge of small numbers and there are major secrecy issues surrounding nuclear weapons strategy and programs. This highlights the importance of our argument. Professional incentives to only study questions that are amenable to certain techniques or access can prevent scholars from exploring key issues. This is not, and we want to emphasize this, an argument against careful research and method, or an appreciation of the limits of what we can claim based on the available evidence. Our point is that if the balance moves too far in one direction then important questions will go unasked. Scholars will conduct ever-narrower studies on issues that aren’t relevant or transferrable to policy problems.

- What was your experience like working with TRIP data?

We have been fortunate to have worked with TRIP on multiple projects. TRIP data is an invaluable tool for understanding broad trends in the discipline and the nature of the academic-policy gap. There is still a lot to be learned from what they have collected.

Preview or buy Bridging the Theory-Practice Divide in International Relations from Georgetown University Press here: bit.ly/Bridging-GUP

Maggie Manson is a junior at William & Mary, majoring in International Relations and Middle Eastern Studies. She began working at TRIP in September 2019. Her research interests include Border Disputes, Colonialism, Global Development, International Security, Middle Eastern Politics, Nuclear Politics, and Political Islam. On campus Maggie is Assistant Chair of Administration for the Undergraduate Honor Council, a research assistant for Professor Grewal’s Armed Responses to Mobilization Or Revolution (ARMOR) project, and Political Correspondent for the Flat Hat student newspaper.