By Mary Trimble

June 29th, 2020

Back in those blissful, bygone days of early March, my fellow RA Peter Leonard wrote a blog post detailing IR scholars’ perspectives on global health, pandemic diseases, and international health institutions. Reading his thorough analysis, one feels the need to hug Peter in sympathy for how his life is about to change and knock IR scholars about the ears for seriously underestimating the gravity of global pandemics– and suggest they all buy stock in Zoom.

Only one week after Peter wrote his blog, William & Mary announced that we wouldn’t be returning from Spring Break. Only a week after that, W&M moved the remainder of the semester online. Just a few weeks before that, my fellow RAs and I had laughed off this possibility as the ravings of an alarmist professor in what would be one of our last in-person gatherings. It goes without saying that all of our lives have been drastically altered by the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s worth addressing, then, how IR scholars’ opinions may have shifted in the face of an actual pandemic, and what that might mean moving forward.

Peter opened his post with this Feb. 24 tweet from President Trump, a useful one that allows us to take stock of where we are now, point by point:

- At the time of writing, the US leads the world’s case count at 2,286,457 and is set to mark the grim milestone of 125,000 deaths by the end of the day (data taken from the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center).

- On May 29, 2020, Trump announced that the US would be withdrawing all funding from the World Health Organization, arguing the WHO is too closely aligned with China, where the virus originated and whose government initially suppressed information about the virus.

- The US stock market has mostly recovered after plummeting more than 30 percent in March, and as of early June the US economy was in a recession. Tens of millions of Americans are out of work as a result of the economic slowdown and shelter-in-place and lockdown orders.

Between April 27 and May 4, nearly 1,000 IR scholars in the US responded to TRIP Snap Poll XIII, which posed questions on the pandemic and the upcoming presidential election. The results of this poll are detailed in this article in Foreign Policy, and the full results can be viewed here.

To begin, it’s worth noting that, on the subject of the WHO, roughly 63% of scholars thought the organization had been “effective” or “somewhat effective” at handling the pandemic, unsurprisingly at odds with the Trump administration’s assessment. This follows, considering Trump is extremely unpopular with IR scholars. If they were voting tomorrow, only 4.9% indicated they would vote for Trump, and in 2016, that number was only at 4%. In 2017, 40% of scholars reported having attended a protest in response to his policies, and that number rose to 60% among women.

IR scholars generally disapprove of the President, and have continued to hold negative views of his handling of the coronavirus crisis (only 4% would pick him in comparison to Joe Biden to handle its aftermath), but it would be unfair to suggest that scholars themselves had been ready for this pandemic. In 2014, scholars from 32 different countries dismissed pandemics as a foreign policy concern (only 3.52% listed it among their top three foreign policy concerns, and an additional 2% of scholars suggested it might be a concern in the next ten years). Based on scholars’ recent responses, however, there seems to be consensus that this pandemic has implications for US foreign policy.

One way of analyzing foreign policy priorities is thinking about spending. When we asked scholars how the US should spend foreign assistance, a majority of scholars supported increases in US spending on economic assistance (62.55%), refugee assistance (77.2%), and, predictably, health aid (a robust 87.86%).

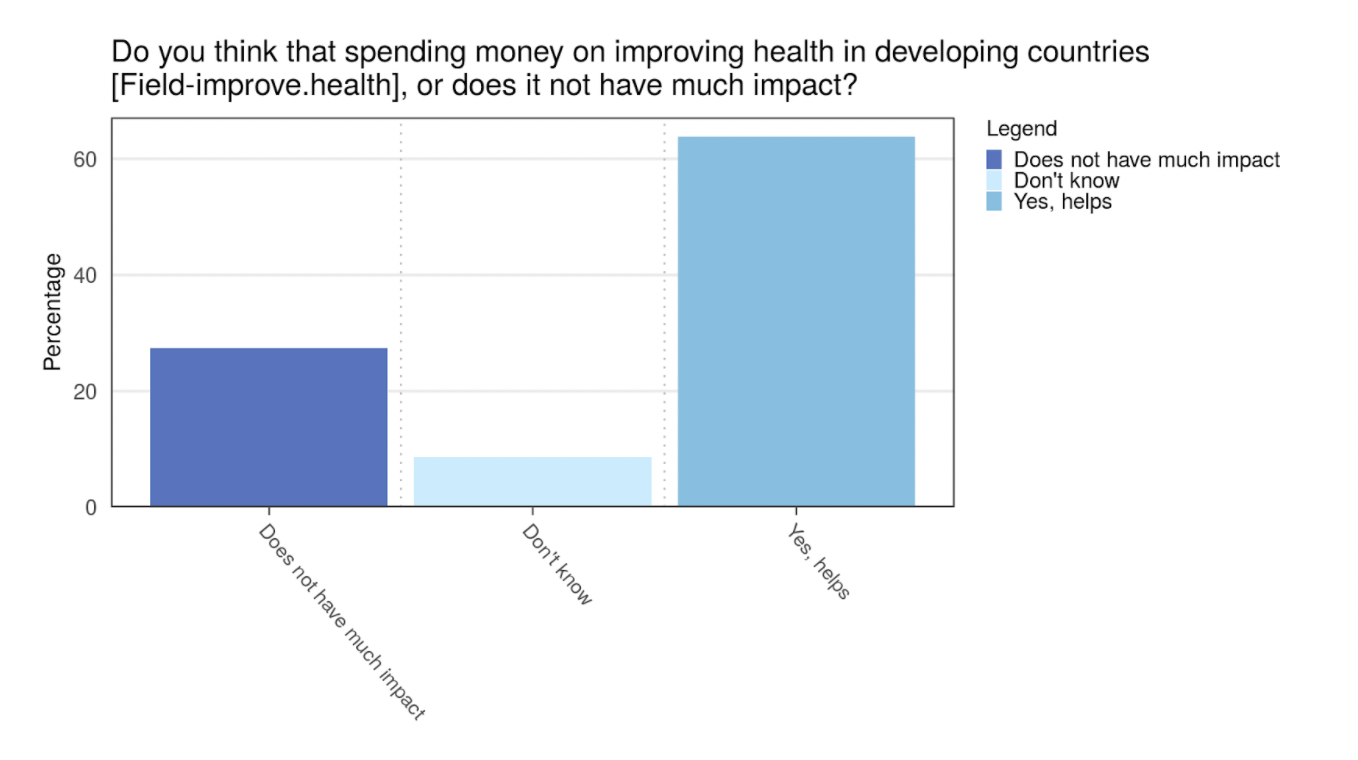

It’s worth considering, however, that COVID-19 may not have much to do with scholars’ responses on aid. These numbers are fairly consistent with their sentiments in 2017. A majority of scholars (63.87%) expressed the belief that health aid improves health outcomes, and even some who thought aid didn’t improve health outcomes still suggested that the US spent too little on health aid.

In the next question, 82 percent of scholars responded that the US spent “too little” on efforts to improve health outcomes in developing countries. It seems logical, then, that in the face of a pandemic which has ravaged even developed countries, the number of scholars wishing to increase health aid to developing countries in 2020 would improve slightly on the number of those who already thought the US was spending too little.

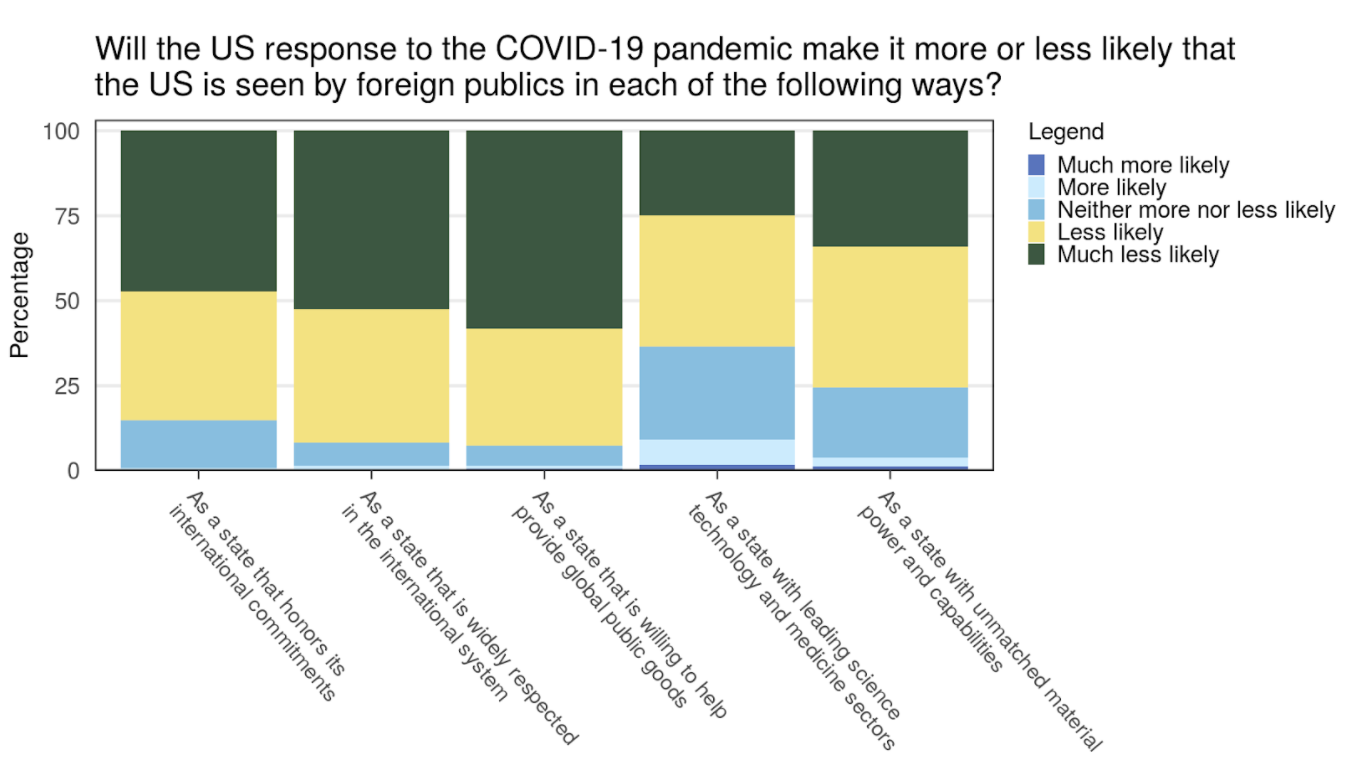

If COVID-19 hasn’t swayed an already aid-friendly audience on the value of aid (in 2017 82% of scholars thought the US was spending too little on foreign aid), perhaps scholars’ opinions on the pandemic’s effect on US soft power may give us a window into how they are thinking about its lasting significance. The TRIP survey asked scholars about how the perception of the US will change among “foreign publics” and “foreign leaders” If you are having trouble telling the graphs apart, you’d be right: Scholars had fairly similar responses as it related to both groups, generally suggesting that a negative reaction to the United States would be slightly amplified among publics as to leaders.

A significant majority of scholars think the US coronavirus response will damage foreign elite and popular opinion of the US as a state that “is willing to help provide global public goods,” “is widely respected in the international system,” “honors its international commitments,” and to a lesser extent, as a state “with leading science, technology and medicine sectors,” and “with unmatched material power and capabilities.” Perhaps some of these metrics may vary as a function of whether or not the US is the country to develop a vaccine, how long it takes to develop, and how freely it is shared– time will tell. In any case, these results seem significant: Scholars predict that US soft power could take a major hit as a result of its handling of the COVID-19 crisis. This must seriously impact how the United States interacts with the international system, right?

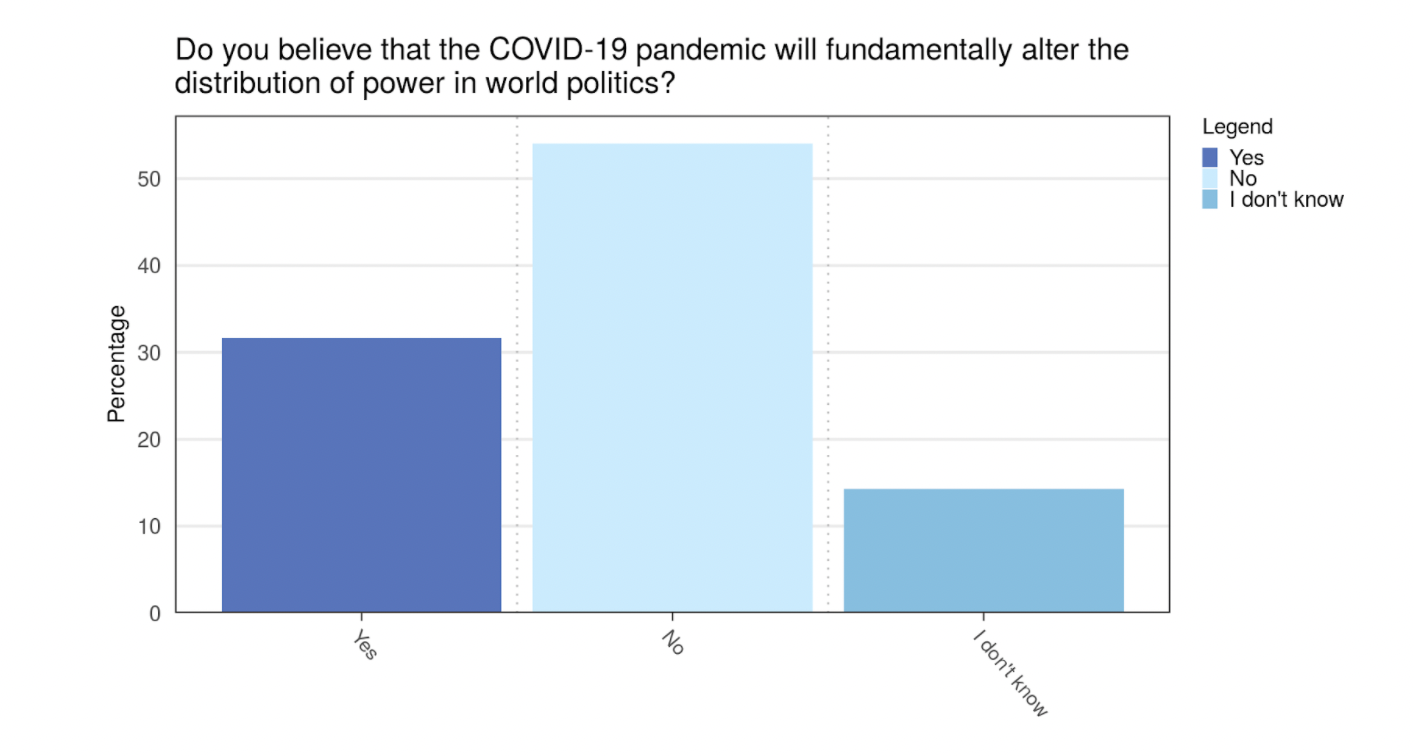

Not so fast. Before we breathlessly herald the end of the US-led liberal world order, scholars also don’t predict this crisis will lead to a major shake-up in the distribution of world power. Perhaps 54% of scholars are skeptical because they judge the blows to US and Chinese power to be roughly equal, or don’t buy that the effects will be long-lasting. For the third of scholars who suggested that the pandemic will fundamentally alter world power politics, maybe it’s because of the US’s bungled response; maybe it’s because of China’s. Maybe, in still another scenario, those scholars predict an effective Chinese soft power offensive, with “Made in China” masks and other personal protective equipment, for example, flying all over the world in an apology by way of public diplomacy. It is, clearly, difficult to say. Perhaps the 14.27% who said they didn’t know were onto something.

In Peter’s blog post, he expressed his hope that “the jolt given by coronavirus helps wake up any IR scholar still sleeping on epidemics.” So did it? The results are… inconclusive. Certainly, there is no one left in the world who will emerge from this period without a keen understanding of the havoc pandemics wreak not just on global health, but also the health of global economies and political institutions. And yet, well over half of the scholars who responded to TRIP’s snap poll said they would not shift the course of their research in response to COVID-19. Only 5% said they were already researching related issues. If a pandemic like the one we are experiencing touches so much of our lives in the modern, globalized world, one wonders why IR scholars don’t seem to be jumping at the chance to ask “Why?”, “How?”, “What happens next?”, and “How can we protect ourselves next time?”

Mary Trimble is a sophomore at the College hoping to double major in European Studies and French and Francophone Studies. Mary began work at TRIP in February 2020. She is also an associate news editor for The Flat Hat student newspaper and a Tribe Ambassador with the Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Her interests include US-EU relations, national identity, and the rise of populism and far-right nationalism in the US and abroad.