By Mary Trimble

October 29, 2020

If you have whiplash from this week’s, this month’s, or even this year’s news cycle, you’re far from alone. The sheer volume of events, that in any other year would dominate cable news for weeks at a time, is enough to leave one’s head spinning and inspire a rather morbid verse of “We Didn’t Start the Fire” (“Ayatollah’s in Iran, do we have a COVID plan?”).

Here’s a quick recap of what has happened in 2020 so far: the assassination of an Iranian general and its fallout (remember that?), an impeachment (almost forgot to include that one), a hotly contested election, a pandemic (which created an economic recession), protests for racial justice, the passing of a legendary supreme court justice, a subsequent nomination fight, and the President of the United States being diagnosed with a potentially fatal respiratory disease (see “pandemic,” above) which, by the way, could have triggered a constitutional crisis. It seems like the only constant in this year— and the thing that has affected all of us, somehow (even scholars in the Ivory Tower)— has been the COVID-19 pandemic.

Naturally, TRIP asked international relations (IR) scholars to try to untangle the Gordian Knot that is the state of 2020. In the fourteenth edition of TRIP’s Snap Polls of IR faculty, 706 IR scholars responded to questions about the upcoming election, foreign policy, and, of course, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Because covering all of their responses would probably require several thousand words and a few degrees that I don’t have yet, we’ll deal here only with scholars’ responses on the pandemic (the people with the degrees have covered the rest of it in this article in Foreign Policy). In Snap Poll XIII, in May 2020, scholars weighed in for the first time on COVID-19 and the US and international response (see the full results here, my take here, and RA Maggie Manson’s analysis of protests in the COVID-19 era using Snap Poll XIII data here).

It goes without saying that much has changed in our understanding of COVID-19 and governments’ containment and mitigation policies since May. Europe and the United States have, for the most part, emerged from a “strict lockdown,” with limited success (and some are locking down once again in the face of a significant second wave). Scientists are scrambling to develop a vaccine, but with flu season approaching and COVID-19 cases rising to record-breaking levels around the world, it doesn’t seem like 2020 is going to end much better than how it started (and it started with the threat of WWIII).

The last six months seem to have been enough to convince most scholars of the serious implications of a pandemic. While in 2017, the overwhelming majority of IR faculty did not believe that infectious diseases were currently a major concern or would become one in the next ten years, this time around, 75% of scholars believed that “the spread of infectious disease poses a major threat to the United States.” (For what it’s worth, this survey was in the field prior to news of the President’s COVID-19 diagnosis.)

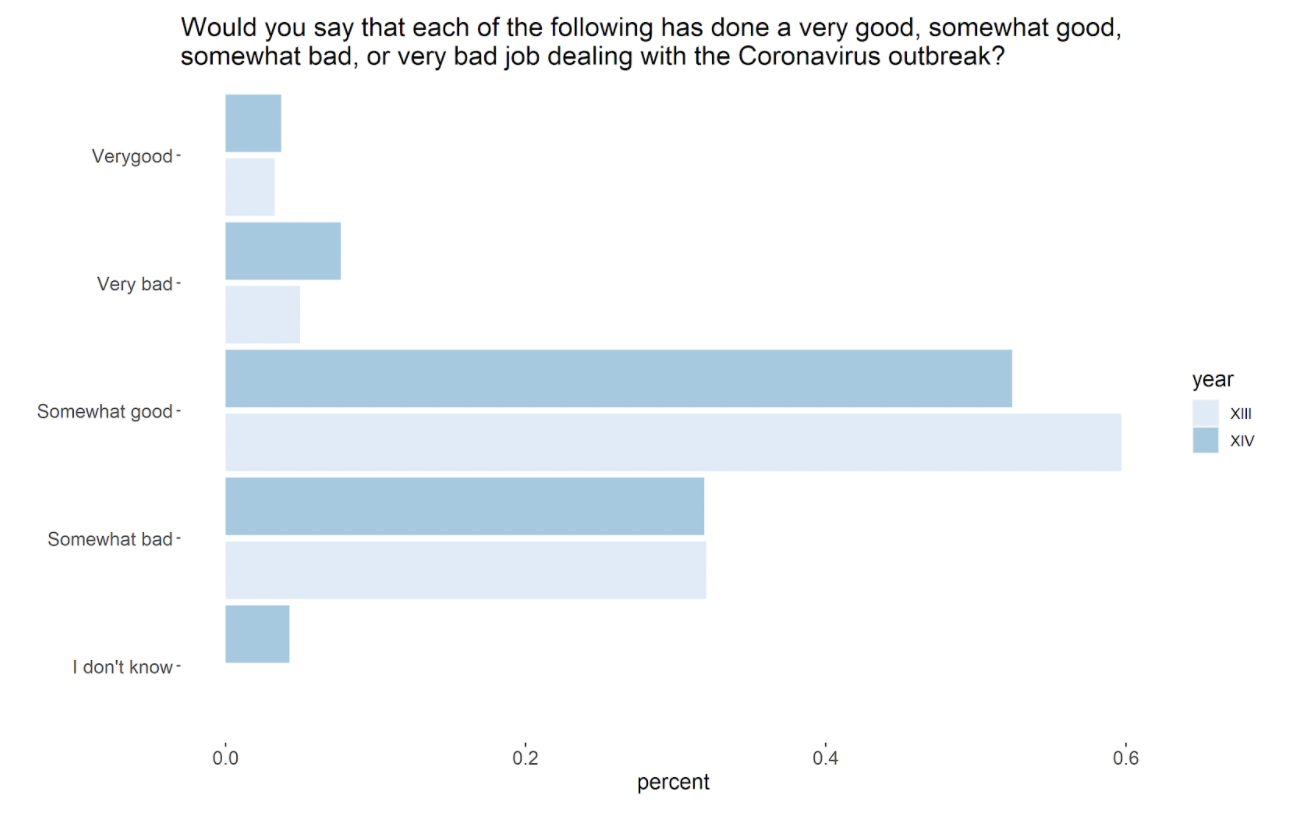

To that end, scholars also chimed in on how they felt governments and institutions had managed that threat. Whereas in May, 63% approved of the World Health Organization’s handling of the pandemic, in Snap Poll XIV, only 55% responded that the response had been at least “somewhat good,” with 32% saying their response had been “somewhat bad.” Perhaps this dip is simply a function of there still being a pandemic all these months later, or perhaps President Trump’s steady drumbeat of negative rhetoric on WHO, including withdrawing US funding from the organization, has penetrated the zeitgeist.

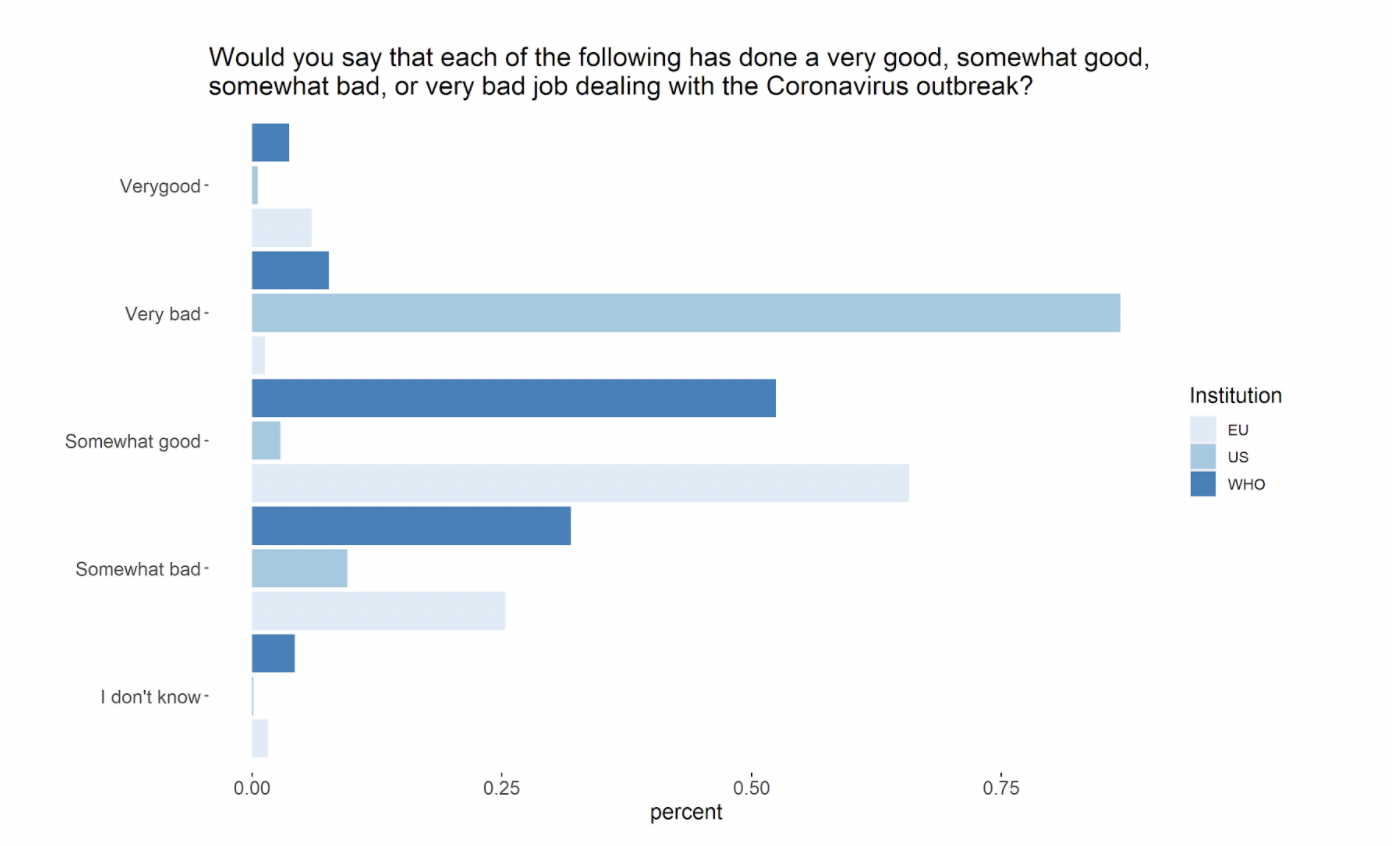

Scholars had a resoundingly dismal review of the US response. Nearly 87% of respondents believed that the US had done a “very bad job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak.” They were much more bullish, however, about the EU’s handling of the outbreak, with roughly 72% saying that the EU had done a “somewhat good” or “very good” job managing the virus.

It’s clear that the Trump Administration has been dismissive of the virus, downplaying the health threats associated with the disease, discouraging public health measures like mask-wearing and social distancing (including and especially at the rallies and events the President has held throughout the pandemic across the country and at the White House), and opposing lockdowns and school closures. In contrast, EU officials have consistently acknowledged the threat of the virus, even when there wasn’t a clear, pan-European consensus about how to handle it.

However, it’s also true that the EU didn’t have immediate (nor consistent) success at handling the virus, by their own admission. Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, scolded member states on March 26, 2020, for their failure to coordinate their responses. “And when Europe really needed to prove that this is not only a ‘fair weather Union’, too many initially refused to share their umbrella,” she said, referencing border closures throughout the Schengen Area and widespread stockpiling of medical supplies by national governments in the early days of the outbreak that disadvantaged other members, including Italy, which was the first European country to see a severe outbreak. Let’s not forget, too, the “corona bonds” crisis that once again pitted Northern and Southern European states against each other.

Yet, in midsummer, when Europe seemed to be past the worst of the virus, the US was seeing its highest case numbers so far. It seemed clear that, at least by the numbers, the EU had gotten something right. Today, the picture is hazier.

As of October 16th, the EU/European Economic Area (which includes the EU-27 and Norway, Liechtenstein, and Iceland) and the UK reported 198,886 deaths (that’s roughly 40 deaths per 100,000). On the same day, the US reported 217,987 deaths total as a result of the pandemic (around 68 deaths per 100,000). In the last week, both the US and the EU have seen significant spikes in the rolling average of new cases. On October 22, the EU and UK saw a 7-day rolling average of 125,571 new cases (25 new cases per 100,000, roughly four times higher than at the peak of the first wave in the spring), and the US reported a rolling average of 59,699 new cases (roughly 18 per 100,000) just under its existing high watermark.

Newsweek reported last week that certain countries in Europe, including Belgium and Spain, have surpassed the US in the number of deaths per one million people. (Moreover, on October 22nd it was announced that former Belgian PM and current Foreign Minister, Sophie Wilmès, was admitted to the ICU after testing positive for the virus.) These numbers suggest that, while perhaps the EU had things under control during the summer, that is no longer true.

Let’s unpack this seeming contradiction in scholars’ opinions and the situation on the ground. First, this poll was in the field between Sept. 16 and 24. At this point, both Europe and the US were experiencing an uptick in cases, but it was much more significant in the United States. We’ve already established that things were looking better in Europe over the summer, while stateside it was nothing but bad news. US scholars are probably also over-exposed to US news, so perhaps no or little news from the EU was taken as de facto good news. So, scholars may have answered based on general and lingering impressions from the situation over the summer. If only to have a reason to use the word “zeitgeist” again, it’s worth reiterating that President Trump’s rhetoric, which has been so consistently at odds with science and public health recommendations, may have contributed to a panic that made anything look better by comparison, even to highly educated, extremely reasonable IR scholars.

IR scholars got it (mostly) wrong this time, it’s true. In fairness, public health science is not necessarily their area of expertise. More importantly, their miscalculation highlights all that we don’t know about this pandemic— the US and the EU took very different tacks in handling the virus and ended up in roughly the same situation. Here, however, is what we do know: masks work, social distancing works, hand washing works. Let’s do those things.

The election is rapidly approaching, and scholars predict that a Biden administration would be vastly different to a second Trump administration in its policy on global public health, among other foreign policy concerns (they predict, too, that Biden would be more effective at achieving those goals). Perhaps that means more collaboration with the EU and others for the development of a vaccine, data sharing, or something else. Beyond that, though, it’s evident that we are far from free of this pandemic, here or across the pond. What’s worse: perhaps we need to evaluate and adjust our and scholars’ standards for what constitutes “success” and “failure” in the context of a pandemic before we have any hope of putting out this fire.

Mary Trimble is a sophomore at the College hoping to double major in European Studies and French and Francophone Studies. Mary began work at TRIP in February 2020. She is also an associate news editor for The Flat Hat student newspaper and a Tribe Ambassador with the Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Her interests include US-EU relations, national identity, and the rise of populism and far-right nationalism in the US and abroad.