By Maggie Manson

April 11, 2022

It has been a little over a year since President Biden took office and quickly began implementing his wide-reaching foreign policy agenda. A regional policy area that should be of great interest to the administration is the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Looking back at some of the major political and humanitarian events that occurred in the region this year, it is interesting to look at the administration’s response, or lack thereof, to these developments. This piece will look back at some of the key events the region witnessed this past year, as well as examine scholars’ thoughts on Biden’s responses to these events.

10 year Anniversary of the Arab Spring

The first notable event of 2021 in the MENA that we will look at was the 10 year anniversary of the Arab Spring protests. While protests in Algeria and Tunisia began in December 2010, the majority of countries involved in protests began in early 2011. This was a landmark movement for the region that resulted in stagnation or minimal reform in some countries, devolution to civil war in others, and full-blown regime change in Tunisia and Egypt.

Some of the key countries where mass protests erupted, but little substantive change followed include Algeria and Sudan. In both of these countries, we saw similar demands and tactics of protesters who took to the streets and social media to call for regime change, economic opportunity, an end to corruption, and much more. While these protests were met with insignificant reform and government repression, they did not signify the end of demands for democratization as we would later come to see a reemergence of protests in Sudan and Algeria in 2019. We will look further into specifically the Algerian protests, also known as the Hirak protest movement later in this piece.

In Tunisia, we saw protests result in the ouster of authoritarian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, accompanied by the emergence of a rich civil society and democratic development. In the period of transition, the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet brought together four different civil society groups to mediate the new democratic process. Tunisia has seen 10 different governments since 2011 with generally free and fair elections and inclusion of a variety of parties. Tunisia has also seen the inclusion of Islamists in governing coalitions as the party Ennahda has been meaningfully included in the political process. Scholars would argue that this inclusion has led to the ideological and substantive moderation of Ennahda, who now labels themselves as Muslim Democrats rather than Islamists. The 2021 political crisis has put a pause to this progress, but we will explore that further soon.

In Egypt, unlike in the previous two countries, initial regime change and democratization backslid into military rule. After the end of the 2011 protests, Egypt saw the emergence of a transitional government and a successful round of parliamentary elections from late 2011 to early 2012. These elections resulted in the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party: the Freedom and Justice party, winning the greatest number of seats as well as the role of Prime Minister. PM Mohamed Morsi and the FJP’s governing coalition were only in power for a little over a year as the military stepped in to remove Morsi and his government in July 2013. This coup d’état lead to the imprisonment, torture, and death of many members of the Muslim Brotherhood which was later deemed a terrorist organization by army chief and eventual authoritarian president General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. While democracy was not sustained in Egypt, this was a unique democratic opening for the country in response to widespread mobilization that will serve as an inspiration for future generations of Egyptians.

What lessons can be learned from these protests ten years out? First, we see the power of social media to amplify movements to an international audience. Social media was becoming a widespread form of communication right at the dawn of the Arab Spring. This allowed protesters to spread their cause worldwide, as well as draw attention to the atrocities committed by the police and military in their repression attempts. The international circulation of these protests also put pressure on foreign governments to intervene. While much foreign intervention was indirect, there were still diplomatic pressures placed on many leaders to either resign or institute reforms to address the demands of protesters. There were also instances of direct foreign military intervention, as seen in Syria where Iran and Russia sided with the regime and Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the U.S. sided with rebel forces. This dynamic also played out in the Yemeni civil war between the Saudi-led coalition and the Iran-back Houthi rebels. Both of these military interventions demonstrate how calls for regime change and reform can quickly devolve into proxy wars between foreign powers who partake in non-humanitarian interventions. The Arab Spring acts as a cautionary tale for foreign intervention where diplomatic intervention led to a positive outcome (i.e. Egypt and Tunisia), but military intervention worked to further destabilize the situation. Additionally, in the context of the Arab Spring protests, it is important to analyze democratic developments, backsliding, and general stagnation, as well as the U.S. response to see where the region is 10 years after sweeping democratic protests. I will explore two post-Arab Spring case studies, Algeria and Tunisia, to see where they stand today in terms of democratization.

2 year Anniversary of Hirak Protest Movement

2021 ushered in the two-year anniversary of the Hirak protest movement in Algeria which resulted in the resignation of former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika and continued calls for further democratic reform. Algeria saw little reform in the wake of the Arab Spring, but protesters took to the streets again in February 2019 to protest Bouteflika seeking a fifth term. These protests resulted in Bouteflika announcing that he would not seek a fifth term and would step down. Instead of this announcement ushering in a new period of democracy, the country’s military-led regime was able to install a new president through rigged elections in late 2019. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune was elected after extremely low voter turnout.

Tebboune was able to utilize the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to crack down on protests, issue a curfew, and altogether ban gathering in large numbers. Despite the regime’s repression, the movement has been able to utilize social media to spread awareness and mobilize in the face of difficulties. In October 2020, protesters re-emerged to commemorate the 1988 October pro-democracy riots, despite a continued ban on protests. Additionally, in February 2021, on the two-year anniversary of the Hirak protest movement, protesters took to the streets to signal that they would not be satisfied with minimal reforms, they wanted an overhaul of the government and the establishment of a lasting democracy.

A key takeaway from the Hirak protest movement is that Algeria needs to reckon with its past before it can establish a democratic future. In a piece I wrote in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, I looked into the lack of transitional justice following the Algerian civil war of 1991-2002. Algerian experts and activists that I spoke with emphasized that the country needs to address its complicated past before it can imagine a democratic future. For additional context, the Algerian civil war occurred in the aftermath of a failed democratic experiment. In 1991, the Islamist group the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was presumed to win parliamentary elections so the military stepped in to cancel elections and reinstate a one-party state. This resulted in the FIS taking up arms against the state in a bloody 10-year conflict where many civilian victims of FIS and military violence disappeared or were killed. Many families still have no idea what happened to their loved ones, and the conflict has been weaponized by the government as a cautionary tale to not disrupt the regime. Any new government that is hopefully able to form from the protests will need to focus on transitional justice in order to heal the still-open wounds of the war.

Tunisian Political Crisis

In July 2021 we witnessed a political crisis in Tunisia where President Kais Saied dismissed the government and suspended the constitution in what critics described as a soft coup. By doing so, Saied essentially delegated all governing powers to himself and his close advisors, rather than the democratically elected parliament. Some of the motivating reasons behind his dismissal of the government were the halting economic conditions, the country’s handling of COVID-19, and accusations of corruption within the government, especially against Ennahda. Protests emerged to push back against this soft coup, but protesters were quickly met with a new curfew installed to curtail demonstrations. Many have drawn parallels between this crisis and the 2013 Egyptian coup d’état, especially given the military’s role in backing Saied. However, there are some key differences between the two cases that hopefully signal a different outcome for Tunisia. First, the actions taken against the government were by an elected official, rather than by a senior member of the military as in the Egyptian case. While Saied’s actions might demonstrate a consolidation of power, he has not entirely dismissed the democratic project. We saw him name Tunisia’s first female Prime Minister: Najla Bouden and called upon her to form a new government. With that being said, Saied has significantly elevated his powers in an unprecedented move since 2011, which demonstrates a salient threat to democracy. By limiting parliamentary power, Saied has made it increasingly difficult for the government to apply checks and balances to his presidential power, which will be a significant barrier to the reinstatement of the constitution.

However, Tunisia has weathered and survived previous political crises since the establishment of democracy, most notably the 2013-2014 political crisis. This event arose from the assassinations of two prominent secular leaders and the rise of Salafist Islamist groups in the country, both of which sparked widespread protests against the governing Troika coalition that prompted Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali to step down. This crisis resulted in the renegotiation of the constitution, which seems to be a likely outcome of the current political crisis as Saied has granted himself constitution-amending powers. The prospects for democracy to emerge from this current crisis might seem grim, but civilians have mobilized and taken to the streets to call for a return to democracy, coming out staunchly against Saied’s actions. These protests have been met with high levels of repression from the police, with the result of many protesters being arrested and/or injured with one recorded death.

Scholars on Biden’s MENA Policy

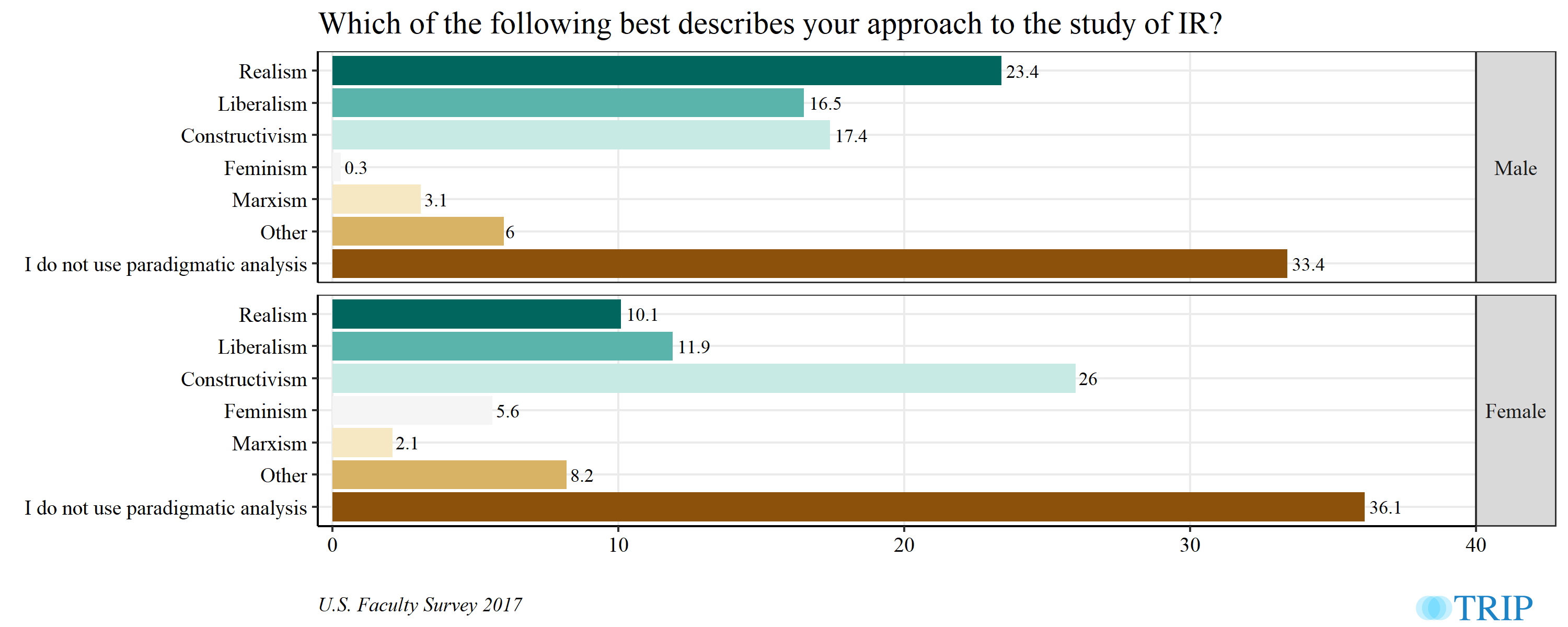

How has President Biden responded to these major events in his first year in office? Biden has promised to shift his focus to the Middle East and North Africa, prioritizing human rights and democracy promotion. Opposite to former President Donald Trump’s approach to the region, Biden has assured that he will not embrace diplomatic relations with autocratic rulers or tolerate governments’ human rights abuses. Expert Steven A. Cook has described Biden’s approach as “ruthless pragmatism” indicating that he will take a practical, realist method to middle eastern policymaking. In regards to democracy promotion in the context of the 10 year anniversary of the Arab Spring, Biden is focusing foremost on improving countries’ human rights records, rather than aiming for direct intervention and regime change.

In Egypt, it is difficult to influence a social and political landscape dominated by the military or the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, notes expert Mohamed Lotfy. This was made worse by Trump’s approach to aid that gave blindly to the regime and also Trump giving into the regime’s rhetoric against the Muslim Brotherhood by declaring the organization as a terrorist group. A useful tactic for the Biden administration will be to utilize aid, both economic and military, in a strategic manner, tying certain conditions to the receiving of aid. The Biden administration should also consider a critical approach to the Brotherhood and other opposition groups that have been the victims of regime violence. This does not entail blanket support of these groups, but instead support for the upholding of their human rights and the end of mass arrests, torture, and even killings of the Brotherhood and other opponents of the SCAF.

In Tunisia, Biden’s response to the current political crisis needs to focus on putting pressure on Saied to reinstate the constitution and re-establish the country’s nascent democracy. Biden also needs to turn his attention toward the stalling economic conditions in the country and its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, both being two key motivations for the protests that led to Saied’s actions. This could look like the provision of U.S. monetary aid meant to alleviate economic woes with conditional terms tied to the constitution being reinstated and Saied committing to upholding democracy. Also, the U.S. should extend its vaccine diplomacy campaign to Tunisia by sending vast amounts of COVID-19 vaccines, as well as medical supplies used to treat COVID cases in order to combat Tunisia’s acute public health crisis.

In regards to the Algerian Hirak movement, Biden first needs to work on strengthening relations with the regime to use diplomacy to work towards democracy in the country. The U.S. and Algeria have strained relations as of late due in part to the establishment of an Israel-Morrocco (Algeria’s neighbor) relationship garnered by President Trump’s decision to acknowledge Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. This relationship has caused distress to Algeria which tends to hold a pro-Palestinian position in regard to the Israel-Palestine conflict. Diplomatic measures suggested for Egypt and Tunisia cannot be a possibility in Algeria until baseline relations are improved.

What do scholars think about Biden’s Middle East policy? In TRIP’s Snap Poll XV, scholars were asked to grade President Biden on his performance in Middle East Policy. Results were generally positive with 30.7% giving Biden a B, 19.1% giving a B+, and 12.8% giving an A-.

This is a good starting point to see where scholars stand on Biden’s Middle East policy, but to further understand their perspectives on this matter, I’ve referred to a survey fielded by the University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll and the Project on Middle East Political Science at George Washington University known as the “Middle East Scholar Barometer.”

When asked to reflect on the Arab Spring and the likelihood that protests will return, 30% of scholars answered that the uprisings are likely to return within the next ten years. Another 46% responded that the uprisings never stopped and are still ongoing in different forms, as we see in the Algerian Hirak movement. These answers are a positive sign for democracy in the Middle East and North Africa as scholars are still generally hopeful about popular uprisings that have the power to inspire change. When asked about the state of U.S. power in the Middle East compared to a decade ago, the results were less positive in terms of U.S. foreign policy goals. 75% of respondents answered weaker than a decade ago, showing that scholars are not confident in the U.S.’s ability to impact change in the region. Nevertheless, given the developments seen in the region in 2021, this year is likely to be an important year for the Middle East and North Africa as the Tunisian political crisis continues to unfold, and the Hirak movement continues to call for regime change in Algeria. Additionally, looking at the outcomes from the Arab Spring ten years later, and given the scholarly opinion that protests are likely to return, we will hopefully see further calls for democracy and human rights in the region. It will be interesting to see how these situations continue to develop and what Biden’s response to them will be.