By Morgan Doll

December 18, 2020

Foreign interference in the 2020 U.S. Presidential election was on many people’s minds after what happened in 2016. Just weeks before the election, news surfaced that Iranian operatives were threatening votes in Alaska and Florida that “they’d better vote for President Trump or else.” A few days later, a Russian hacking group was alleged of conducting cyberattacks on U.S. government infrastructure where they broke into at least two counties’ government servers accessing voter data. Reports show that efforts by foreign adversaries are unlikely to have affected the actual count of votes, but they were able to create doubt about the conduct of the election and spread false information to influence voters.

Foreign interference in U.S. elections is nothing new to our history. France historically sought to influence American presidential elections by appealing to the American people against the Federalists during the 1700s. In 1940, Great Britain wanted the United States to join the war to help boost their odds of winning. Since FDR was more supportive of the war effort than his opponent, British agents spread propaganda about FDR’s opponent to ensure a pro-war win. Interference is not just an issue in the United States; it is prevalent throughout the Western world, and globalization plays a huge role. As our world becomes more interconnected, foreign actors have more of an incentive to have the right candidate for them in office. For example, if one candidate supports trade policies that would favor certain countries, then those countries would have an incentive to elect the candidate that would help them economically. But the United States is no victim either. The U.S. government is notorious for interfering in Latin American elections to prevent left-leaning governments from coming to power.

Given the international-domestic nexus of foreign interference, how should the United States best protect their elections and ensure that the American public is confident in the current election system?

Where to start to protect our elections

The act of election interference defies the main principle of international law that countries must “respect the political independence and socio-economic and cultural integrity of every state.” NATO has clear rules on election interference stating that “cyberattacks and election interference will be regarded as a violation of the Article 5 mutual defense provision,” which encourages NATO allies to respond collectively against an attack on one of their members. Additionally, because cybersecurity is a crucial aspect of election interference and international security today, many see the issue primarily as an international one that needs to be met with an international response.

Countries often respond to the threat of election interference through international measures such as economic sanctions, but many countries have also responded domestically by creating agencies within the country to combat foreign election interference and outlawing campaign donations from foreigners. In response to the spike of Russian active measures in the 2016 election, President Trump signed an executive order in 2018 that would place sanctions on any foreign entities proven to interfere in U.S. elections. Other countries such as Australia, France, Japan, and Canada decided to limit or prevent foreign donations to specific parties and candidates. Sweden created a government agency to increase awareness surrounding threats of misinformation, and made a manual for the public to combat influential activities by foreign powers. The United States, similarly, has worked to toughen America’s election infrastructure, and the FBI along with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency have kept up a drumbeat of regular bulletins about what they call the latest intelligence about prospective election cyberthreats. It seems as though these measures have been somewhat effective, considering how quickly the intelligence community was able to catch the interference by Iran and Russia before the election.

Countries often respond to the threat of election interference through international measures such as economic sanctions, but many countries have also responded domestically by creating agencies within the country to combat foreign election interference and outlawing campaign donations from foreigners. In response to the spike of Russian active measures in the 2016 election, President Trump signed an executive order in 2018 that would place sanctions on any foreign entities proven to interfere in U.S. elections. Other countries such as Australia, France, Japan, and Canada decided to limit or prevent foreign donations to specific parties and candidates. Sweden created a government agency to increase awareness surrounding threats of misinformation, and made a manual for the public to combat influential activities by foreign powers. The United States, similarly, has worked to toughen America’s election infrastructure, and the FBI along with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency have kept up a drumbeat of regular bulletins about what they call the latest intelligence about prospective election cyberthreats. It seems as though these measures have been somewhat effective, considering how quickly the intelligence community was able to catch the interference by Iran and Russia before the election.

What do IR scholars think?

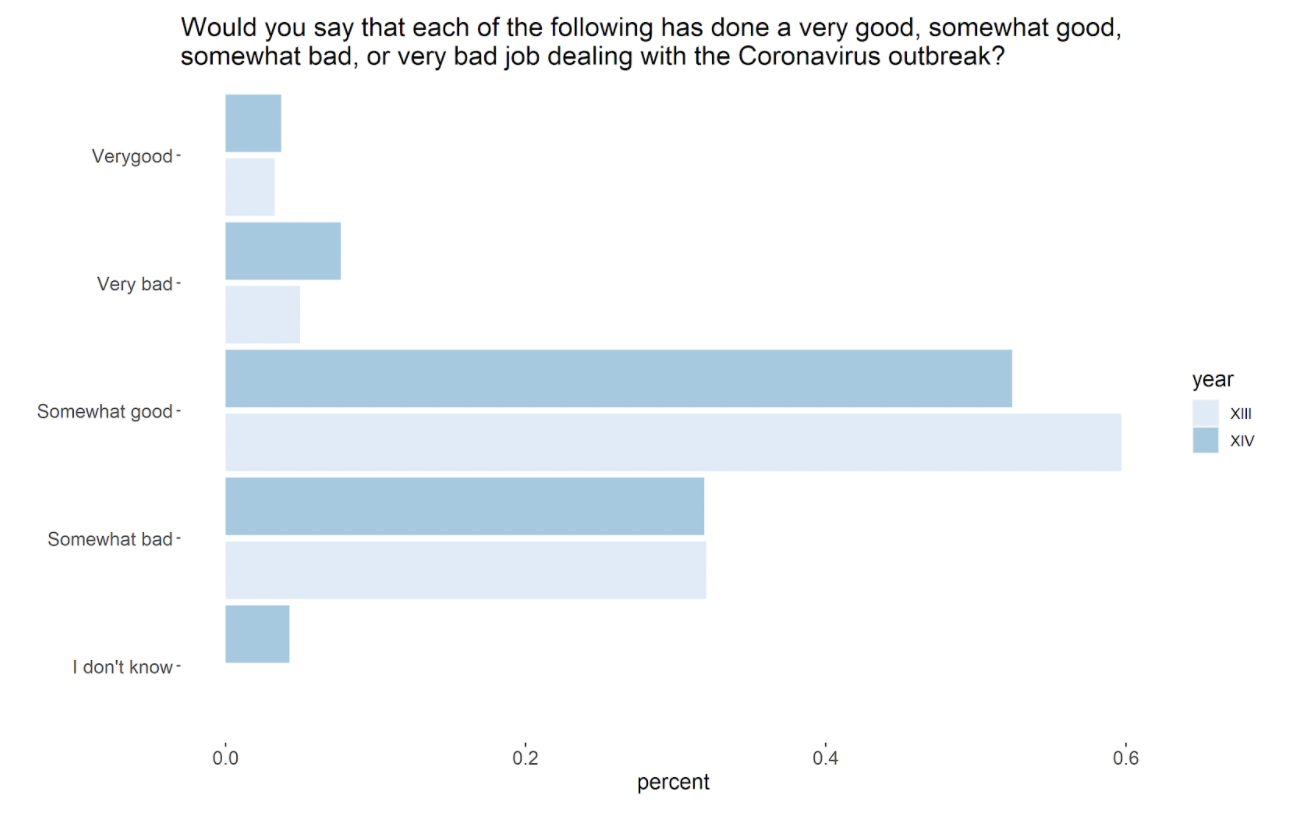

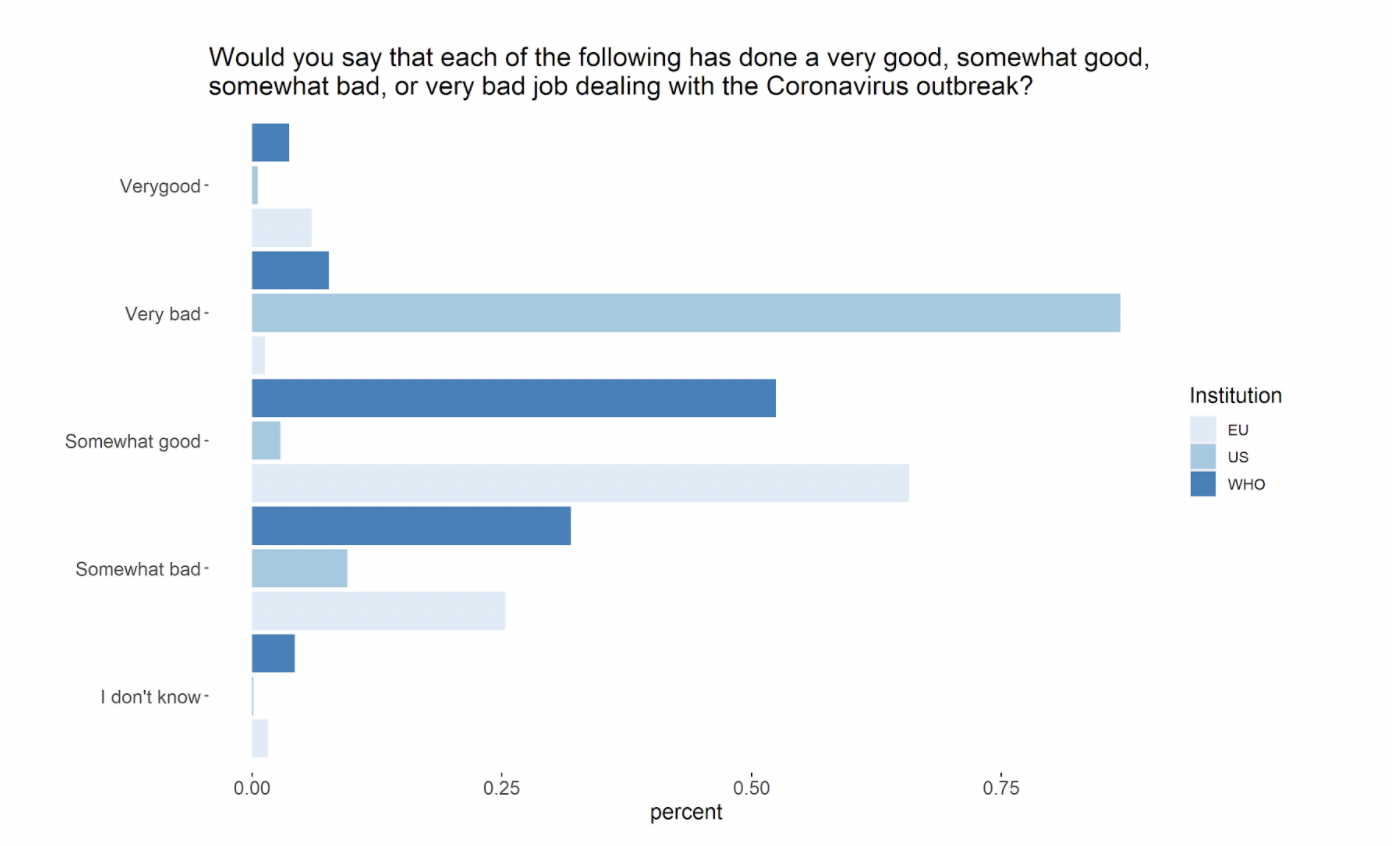

In Snap Poll XIV, we polled I.R. scholars to see how a handful of U.S. policies would affect the probability of interference by foreign governments in future U.S. elections. 79% of scholars said that enhanced cybersecurity measures for election infrastructure and enhanced counterintelligence efforts would decrease the probability of interference. 70% of scholars said that enhanced election finance laws would decrease the probability of interference. 67% of scholars said that deterrent threats of diplomatic isolation would have no effect, while 47% of scholars believe that deterrent threats of retaliatory economic sanctions would have no effect. The least effective measure chosen by scholars was deterrent threats of retaliatory military force, as 61% said there would be no effect and 14% said this would increase the probability of interference.

From these findings, we can see that scholars believe domestic leaning, defensive policies, like election finance laws, infrastructure, and counterintelligence efforts would be more effective than international leaning, retaliatory policies, like threatening cyberattacks, military force, and economic sanctions. Thus, while foreign election interference may seem like a primarily international issue, a combination of domestic policies and international cooperation might best combat this issue in future elections.

From these findings, we can see that scholars believe domestic leaning, defensive policies, like election finance laws, infrastructure, and counterintelligence efforts would be more effective than international leaning, retaliatory policies, like threatening cyberattacks, military force, and economic sanctions. Thus, while foreign election interference may seem like a primarily international issue, a combination of domestic policies and international cooperation might best combat this issue in future elections.

An anonymous essayist in the late 18th century who signed his name as “National Pride” wrote, “if the choice of a President of the United States is to depend on any Act of a foreign nation, farewell to your liberties and independence.” Foreign interference in elections will only become a bigger issue as globalization increases and technology advances, so countries should begin building their defenses now, and world powers like the United States should be punished for interfering in smaller countries.

Morgan Doll is a junior at the College of William and Mary majoring in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. She started working as a Research Assistant for TRIP in September 2019. On campus, Morgan is a member of Camp Kesem William & Mary and Kappa Alpha Theta Women’s Fraternity. Her interests include human and civil rights, law, and decision making. Skills: Foreign Language (Spanish)