By Morgan Doll, Maggie Manson, and Mary Trimble

July 7th, 2020

On Thursday, February 27, John Mearsheimer, the Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago, delivered a talk called “America’s Delusional Foreign Policy during the Unipolar Moment.” The talk was co-sponsored by the John Quincy Adams Society and the Global Research Institute. In the following weeks, TRIP Research Assistants wrote about their thoughts in response to the talk. Campus deactivation due to COVID-19 prevented us from posting their reactions until now.

Morgan Doll’s Response

According to TRIP’s 2017 Faculty survey, many IR scholars believe that John Mearsheimer has been one of the greatest influences on the field of IR in the past 20 years. We wanted to see how Mearsheimer’s arguments compared to what other International Relations scholars think by using TRIP data from snap polls IX, X, and XI.

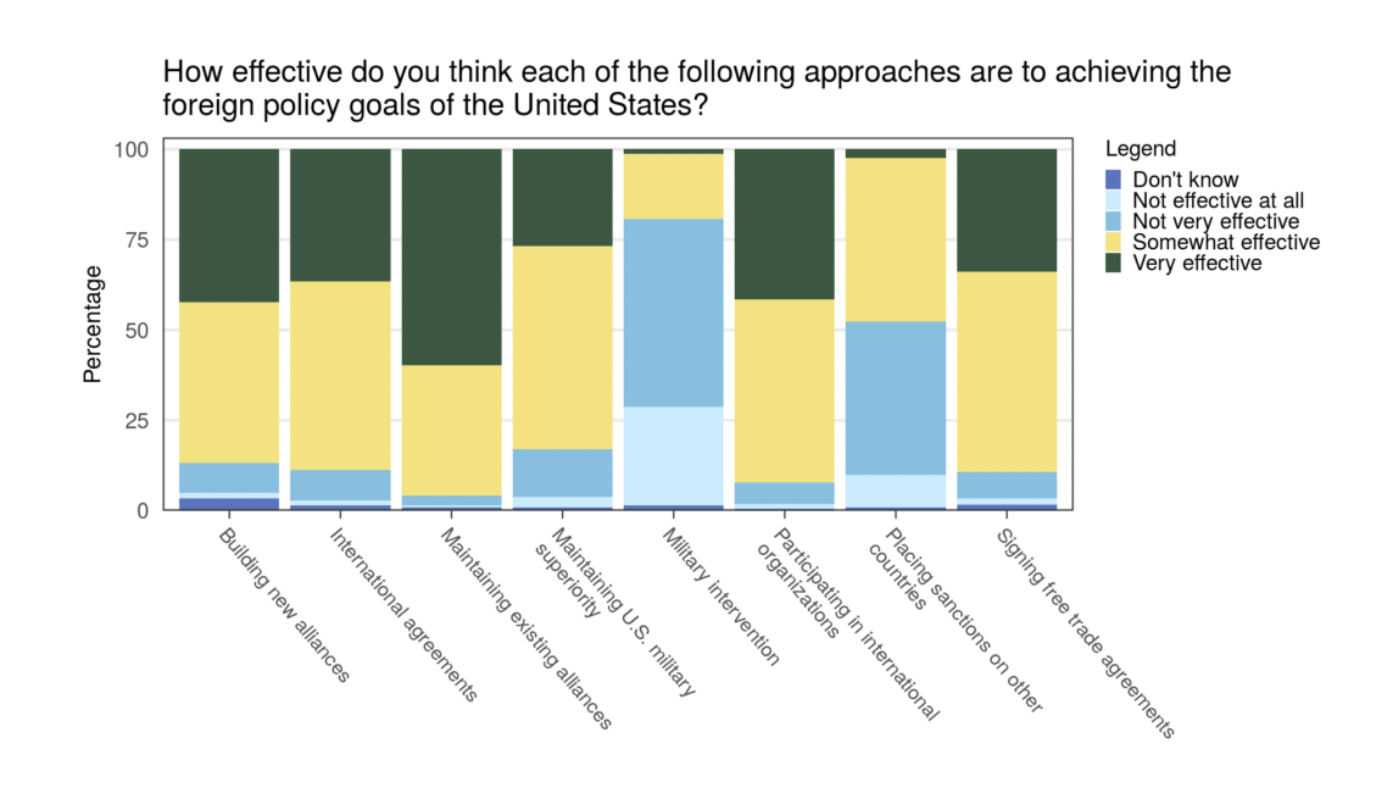

- How effective do you think each of the following approaches are to achieving the foreign policy goals of the United States?

Scholars agree with Mearsheimer’s argument that the United States’ foreign policy approach of military intervention was not effective in achieving the foreign policy goals of the United States. The vast majority of scholars also agree with Mearsheimer that participating in international organizations is very to somewhat effective.

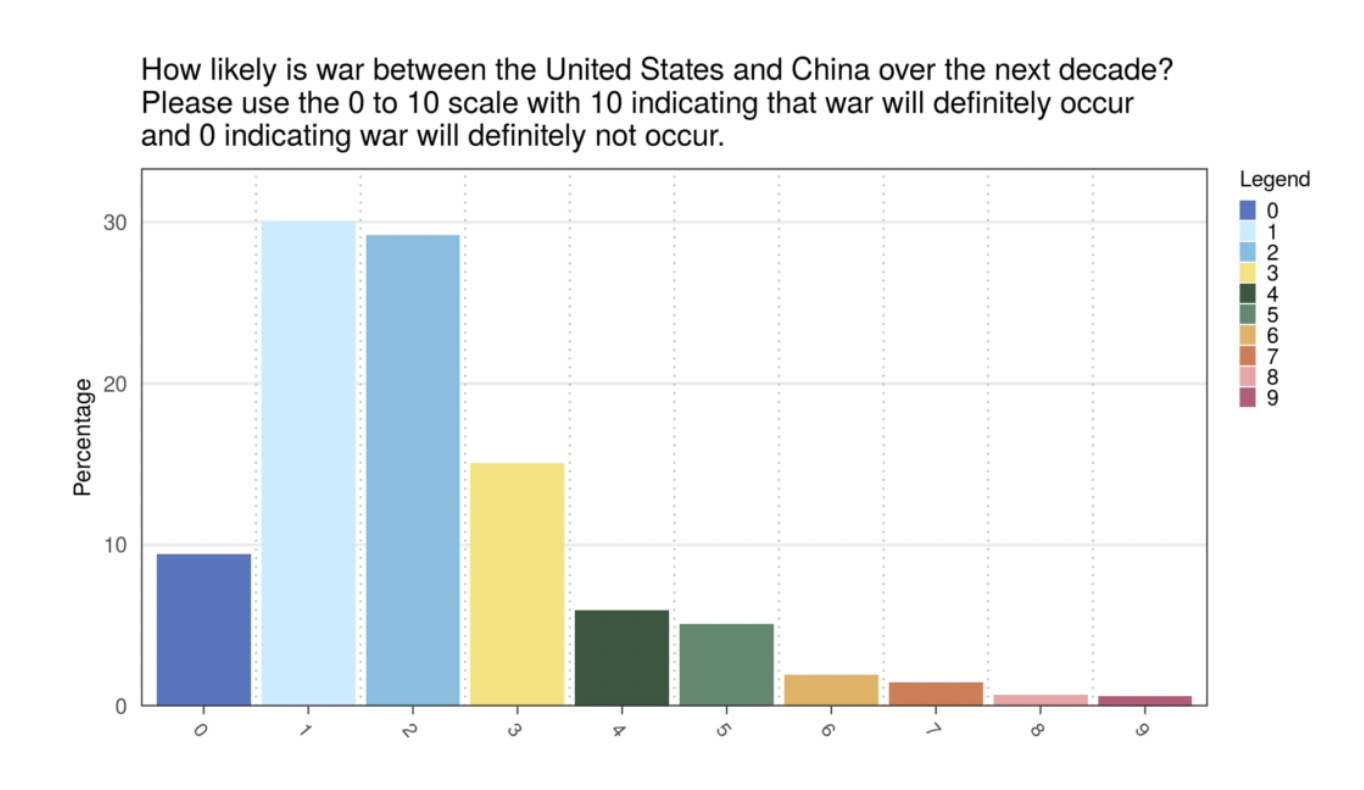

- How likely is war between the United States and China over the next decade? Please use the 0 to 10 scale with 10 indicating that war will definitely occur.

In his talk, Mearsheimer discussed how U.S. engagement with China backfired for the U.S. and led to China becoming one of the three current world powers. Mearsheimer believes that the rise of China will be a major international security concern and is unlikely to be tranquil. Interestingly enough, the majority of IR scholars think that war with China in the next decade is unlikely with 92.13% of scholars rating war with China a 5 or less out of 10.

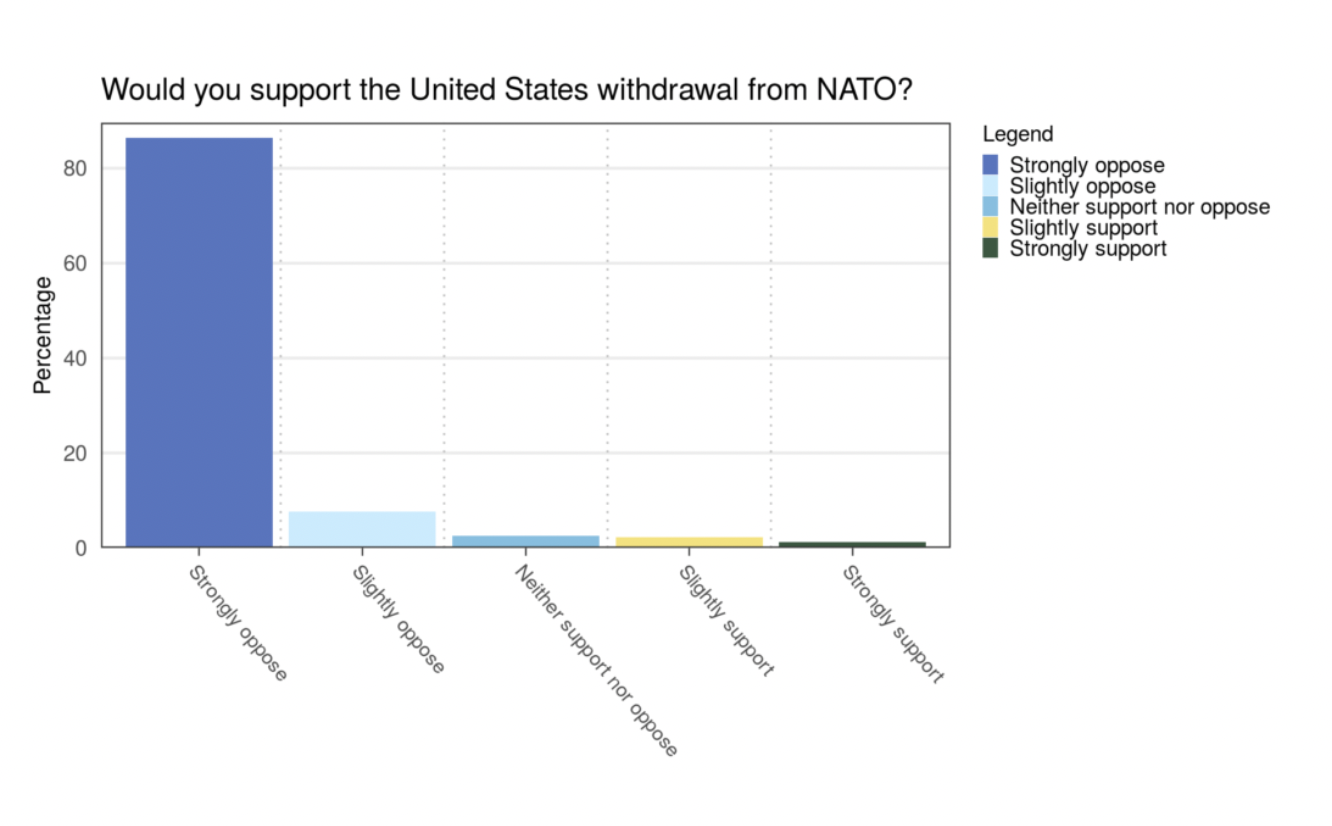

- Would you support the United States withdrawal from NATO?

Mearsheimer’s focus was centered on the U.S.’s foreign policy decisions and how this has affected the state of the world today. One of his arguments was that NATO was responsible for the Ukraine crisis. Even though he is a proponent of realism, he believes that at this point all institutions and international organizations are indispensable. Especially with the resurrection of Russia as an international power, he and scholars agree that they strongly oppose U.S. withdrawal from NATO.

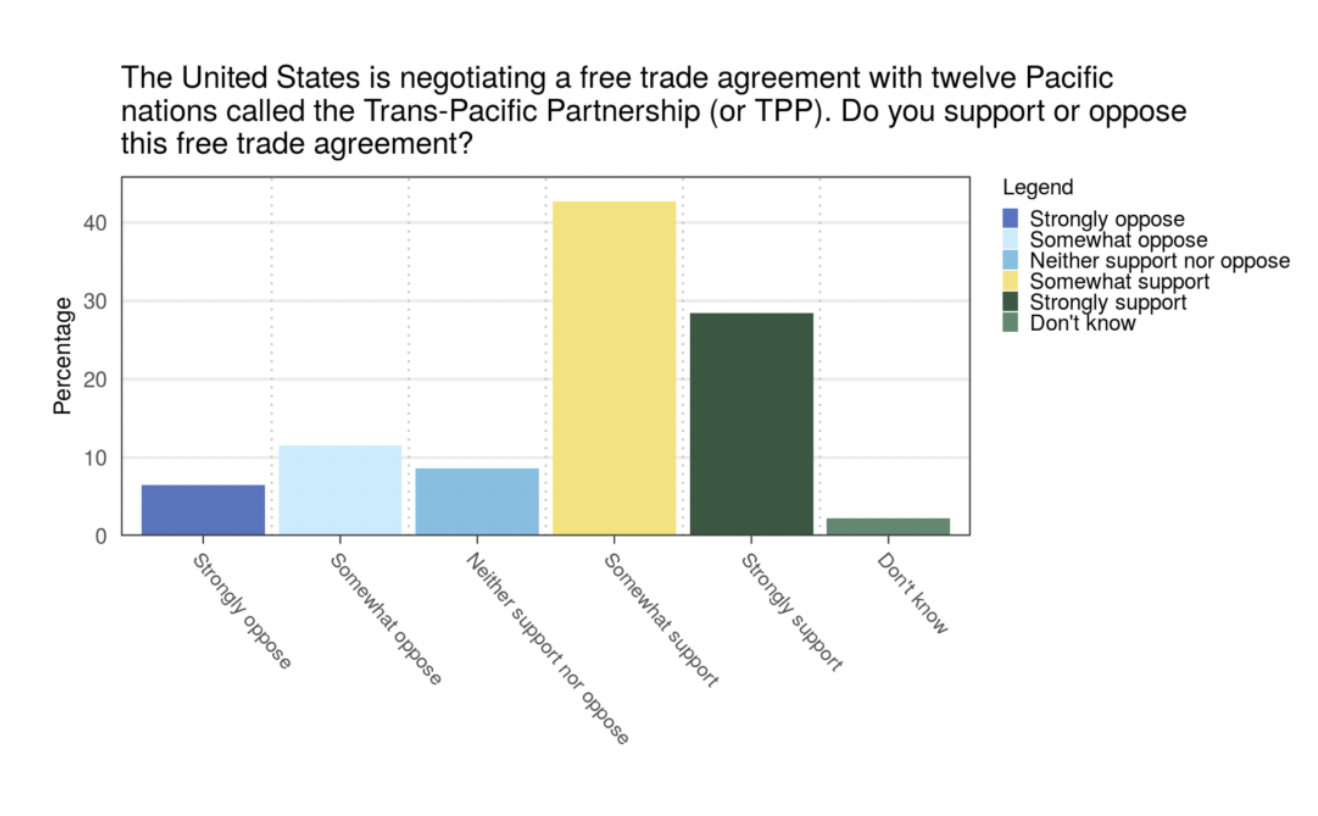

- The United States is negotiating a free trade agreement with twelve Pacific nations called the Trans-Pacific Partnership (or TPP). Do you support or oppose this free trade agreement?

Mearsheimer noted that there is a tendency to describe Trump as a realist politician. He disagrees with this notion and a lot of Trump’s policy; for example, he believes that Trump should not have pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership along with many IR scholars who oppose many of Trump’s signature foreign policy decisions. Mearsheimer additionally argued that the reason why Trump is in the White House and why Bernie Sanders is doing relatively well in Democratic primaries is because of the bad U.S.FP decisions made in recent history. American citizens are in a period where they crave more non-interventionist candidates who seek to change the present system.

Maggie Manson’s Response

During Professor John Mearsheimer’s talk: “America’s Delusional Foreign Policy During the Unipolar Moment,” which corresponded with the release of his new book The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities, Mearsheimer outlined the basic tenets of liberalism, nationalism, and liberal hegemony. He argued that nationalism was the most powerful political ideology on the planet and that it was a sharp refutation of liberal hegemony. According to Mearsheimer, liberal hegemony, which entails the spread of democracy and the integration of countries into the international economy and international institutions, has long guided United States Foreign Policy (USFP). He described U.S. state-building in the Middle East, U.S. intervention in Eastern European democratization efforts, and U.S. engagement with China as key examples of liberal hegemony. Mearsheimer argued that these examples ultimately demonstrate the failure of liberal hegemony, on account of the power of nationalism, realism, and the overselling of individual freedoms by liberal hegemony.

After the talk, I asked Professor Mearsheimer: “In the opposite fashion of the Bush doctrine, how would U.S. aid for dictatorships in the Arab world (as a response to a fear of Islamism) fit into this idea that USFP has centered on liberal hegemony in recent years?” My logic behind this question was that if the Bush doctrine and the idea of liberal hegemony centered on the spread of democracy, then why would the U.S. provide aid to dictatorships, and what paradigm would these actions then align with? Mearsheimer replied that he did not believe that fear of Islamism was a factor that played into the promotion of dictators by the U.S. and that extremist fears were not necessarily relevant to those considerations. When referencing Islamism I was referring to political Islam, not terrorism, so clarification on my end could’ve helped. However, he went on to say that the reason for such actions would be that the U.S. was supporting U.S.-friendly dictatorships to bolster its own interests, not democracy. While I agree that state interests could be an explanatory factor for U.S. support of dictatorships, I believe that this explanation is incomplete without factoring in the fear of the rise of political Islam that could occur through the promotion of democracy in the Middle East. Promotion of democracy would otherwise better fit the U.S.’s interests if it was not concerned about Islamism in a democratic middle east. Also, his answer appeared to be contradictory to his previous reference of the Bush doctrine as a prime example of liberal hegemony because that doctrine centered on the spread of democracy which is not reflected through the promotion of dictatorship, even if it better serves American interests. I did find Professor Mearsheimer’s talk to be extremely interesting and engaging, despite my disagreement with his answer.

Mary Trimble’s Response

“It’s all going to be peace, love, and dope.” That was how John Mearsheimer, world-renowned realist international security scholar, characterized the U.S. policy of liberal hegemony in the post-Cold War era during his public lecture at William & Mary on Feb. 27. In his fairly comprehensive look at the relative success or failure of the U.S. project to “remake the world in its image” by democratizing nation-states, he concluded that the policies of liberal hegemony were a failure because the forces of realism and nationalism are so much more potent in the international system. After some consideration, I realized that none of what he presented was the argument I expected him to make. Despite decades of describing the world in realist terms, even outlining his own theory of offensive realism as an explanation for state aggression, he seemed, in his lecture, to assert that the U.S. was not a realist, rational actor in the unipolar moment since it was no longer constrained by balance-of-power politics and strategy. Here is, then, what I would have expected him to argue, and how it compares to what he did say.

Mearsheimer’s theory of offensive realism is predicated on the assumption that states are rational actors, and as such, try to maximize their power in the international system (which is anarchic, or without a central authority or formal hierarchy). But he didn’t start here when describing the U.S. pursuit of liberal hegemony in the unipolar moment. Rather, his assumption was that they pursued this policy based on an overwhelming belief in liberalism, rather than rational self-interest. He seemed to assign a certain moral clarity to the United States– even if the policies were wrongheaded (and resulted, according to Mearsheimer, in the longest war in the U.S. history and hundreds of thousands of casualties in the Ukraine Crisis, and in the rise of China), at least our heart was in the right place. In some ways it’s reassuring; one can almost forgive making a mess if someone was only trying to help. The U.S. does express a commitment to universal human rights, democracy as a social contract, and democratic peace. Mearsheimer argued that unipolarity allowed the United States to pursue that commitment with gusto, to create liberal hegemony in the world where the U.S. was “Godzilla surrounded by Bambi.” In his talk, he argued that unipolarity created the conditions for liberal hegemony. What I thought he would say was that the U.S. pursued liberal hegemony because liberalizing creates countries that think as the U.S. does, that engage in the international system of finance and norms like the U.S. does, and over whom the U.S. might have more influence as the head of that system in a unipolar world. Ultimately, I assumed he would say that the U.S. foreign policy in the nineties and aughts was a manifestation of the U.S. desire to maximize their power in an anarchic international system when no other power was around to stop them.

Mearsheimer pointed to the Bush Doctrine push to create liberal democracies in the Middle East as a result of the liberal hegemonic project. Maggie made an interesting point in her question to him, and in her own contribution to this post. To address Maggie’s point about the U.S. involvement in the Middle East, it seems like Mearsheimer’s own ideas of realism is the most effective at explaining various U.S. foreign policy positions in the region, not liberal hegemony defined as the univocal striving for the creation of liberal democracies. The United States has long supported Saudi Arabia as a close and relied-upon ally, despite their authoritarian rentier system and a disastrous human rights record, most infamously on gender equality and press freedom, to name only two. For another example, take U.S. support of Egypt under Hosni Mubarak, who, while maintaining a tenuous peace with Israel, ruled with an iron fist with the support of a vast police state until his ouster during the Arab Spring. Why would the U.S. support these regimes if it was all-in for liberal hegemony, as Mearsheimer asserts? In reality, it seems more reasonable that the U.S. supports its allies who stand with them (whether against Iran in the case of Saudia Arabia, or in peace and stability with its other ally Israel in Egypt’s case), and does so in a manner more realist than liberal.

Mearsheimer’s ultimate argument seemed to be that the U.S. is not a realist country, and was instead motivated by a belief in liberalism. I’m not necessarily trying to say he’s wrong, only that his argument doesn’t follow logically from his many years of scholarship in international relations. But, his willingness to continue to write, engage in discussion in publications like The New York Times or Foreign Policy and to lecture to college students like me speaks to his status as a public scholar, as Professor Peterson noted in her introduction to his lecture. The ability to think critically about the arguments he proposes, and to dispute them, when necessary, allows us to inch closer to the truth in the study of international relations.

Morgan Doll is a junior at the College of William and Mary majoring in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. She started working as a Research Assistant for TRIP in September 2019. On campus, Morgan is a member of Camp Kesem William & Mary and Kappa Alpha Theta Women’s Fraternity. Her interests include human and civil rights, law, and decision making.

Maggie Manson is a junior at William & Mary, majoring in International Relations and Middle Eastern Studies. She began working at TRIP in September 2019. Her research interests include Border Disputes, Colonialism, Global Development, International Security, Middle Eastern Politics, Nuclear Politics, and Political Islam. On campus, Maggie is Assistant Chair of Administration for the Undergraduate Honor Council, a research assistant for Professor Grewal’s Armed Responses to Mobilization Or Revolution (ARMOR) project, and Political Correspondent for the Flat Hat student newspaper.

Mary Trimble is a sophomore at the College hoping to double major in European Studies and French and Francophone Studies. Mary began work at TRIP in February 2020. She is also an associate news editor for The Flat Hat student newspaper and a Tribe Ambassador with the Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Her interests include US-EU relations, national identity, and the rise of populism and far-right nationalism in the US and abroad.