By Aidan Donovan

October 8th, 2019

The ideological divide between International Relations scholars varies greatly between foreign policy issues. Understanding which issues appear to stimulate strong ideological fissures allows us a measure of healthy skepticism when interpreting surveys of scholars. Consumers of academic knowledge should withhold some confidence in scholarly claims until we better understand how scholars arrive at their conclusions. On issues where ideology may cause differing views, we should acknowledge this difference when evaluating overall conclusions, particularly since IR scholars are mostly liberal.

The Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) Project’s 2017 Snap Poll includes responses from 1,395 IR scholars at U.S. colleges and universities. In our sample, 181 scholars identify as somewhat or very conservative on economic or social issues. The large sample of IR scholars allows us to examine the ideological divide within the academy and provide initial support a potential causal relationship between ideology and views on certain issues.

The divide is present on some of the issues we asked scholars to evaluate. First, we asked scholars if they approved or disapproved of “President Donald Trump’s proposed policy of withdrawing U.S. support” (1) from the Iran nuclear weapons agreement and (2) for international climate change agreements. Finally, we asked scholars if they believe that ISIS is a major threat to the United States. According to basic logistic regression models, the apparent role of ideology varies among these issues.

A simple logistic regression of approval to leave the Iran Deal on conservative ideology estimates that conservative scholars are 60 times more likely to support this policy than non-conservative scholars. Ideology explains about a third of the variation in support, suggesting this may be an ideologically salient issue. Iran is a controversial country and has a complicated history with America and its allies, so American perceptions of the deal are deeply partisan.

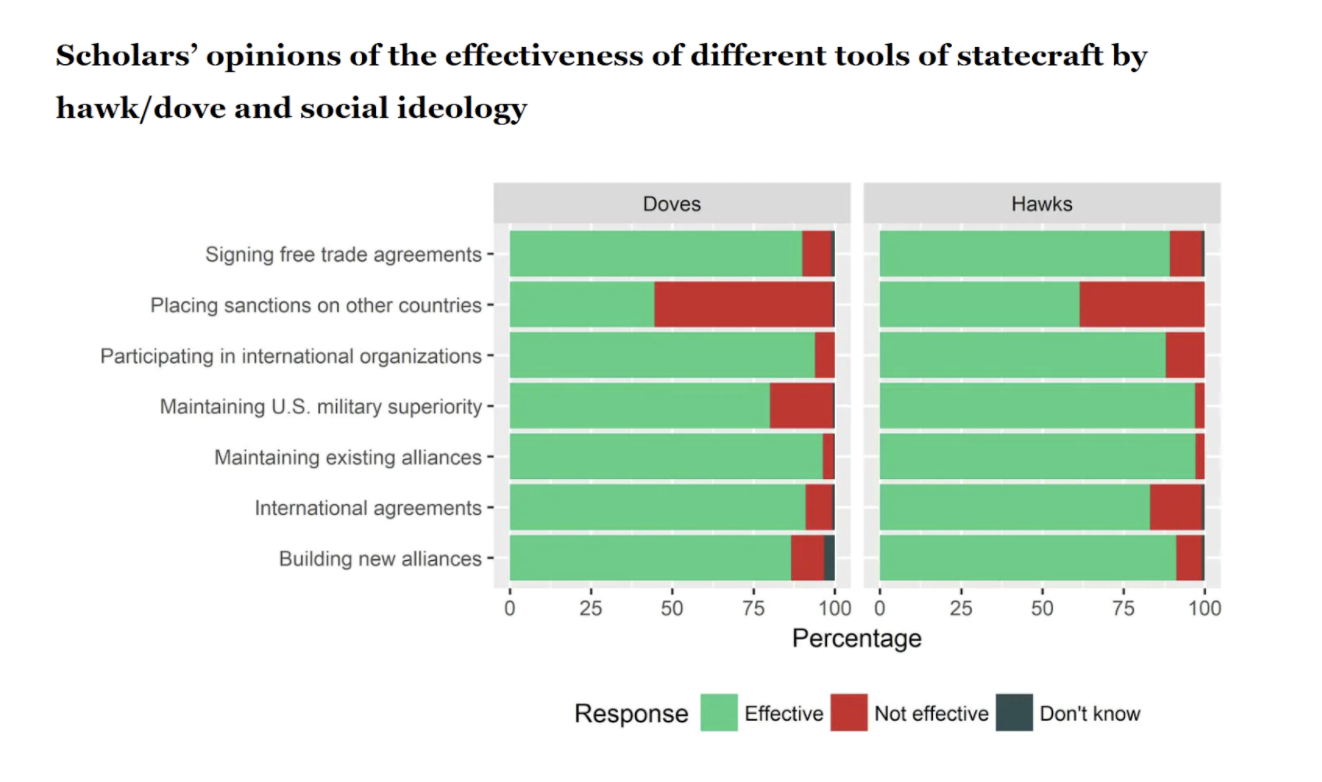

The next step is to control for factors separate from deep-seated political ideology. The deal relaxed sanctions on Iran and frustrated Israel, an American ally. Therefore, I first controlled for individuals’ belief in the effectiveness of sanctions and maintaining existing alliances as foreign policy tools of the United States. The power of ideology increased slightly, and neither of the foreign policy controls were statistically significant. Next, I included the perceived effectiveness of international agreements and military intervention, since that is often presented as the forced trade-off here. Both of those controls are significant, but conservatives are still 28 times as likely as non-conservatives to approve of Trump’s proposal.

I want to examine different ideological perspectives, so I finally control for confidence in President Trump “to do the right thing regarding world affairs.” Conservative scholars are about 11 times more likely than non-conservative scholars to approve of Trump leaving the Iran nuclear agreement, even controlling for the policymaking controls and confidence in President Trump.

An ideological divide is also present on President Donald Trump’s proposed policy of withdrawing U.S. support for international climate change agreements. A simple logistic regression estimates that conservatives are almost 80 times as likely as non-conservatives to support this policy. Almost half the variation in support for withdrawing U.S. support for climate agreements is explained by ideology.

I add controls for the perceived effectiveness of international agreements and international organizations and the ideology gap decreases to 54 times as likely. Belief in international organizations has a statistically significant and negative relationship with approval of this policy. This is unsurprising since the largest climate agreements, notably the Paris Agreement, are negotiated through the United Nations.

Finally, the full model controls for confidence in President Trump as well. Conservative scholars in our sample are about 26 times as likely to approve of withdrawing U.S. support for international climate change agreements than non-conservative scholars, controlling for confidence in Trump, international agreements, and international organizations. Scholars who are confident in Trump are 7 times as likely to support his climate policy. The variation between these estimates show that ideology appears to play a role in scholars’ beliefs on key questions in international affairs, even beyond their expressed political preferences.

However, the role of ideology, and its relationship with political preferences, is not consistent on all issues. A simple logistic regression between scholars’ belief that ISIS is a major threat and ideology finds no significant relationship. In fact, ideology explains less than 1 percent of their perceived threat of ISIS. A hawkish attitude, measured by confidence in military intervention to achieve U.S. foreign policy goals, appears to matter. However, even this relationship breaks down when controlling for confidence in President Trump. Candidate Trump ran on an anti-interventionist stance, but scholars with confidence in Trump are more likely to view ISIS as a major threat than those without confidence in Trump, even though ideology is statistically and substantively insignificant.

Some foreign policy issues, such as climate change agreements and the Iran nuclear deal, appear to stimulate ideological differences in how scholars view the issues and possible solutions. If ideology causes scholars to hold differing views, we must acknowledge this difference when evaluating overall conclusions. Understanding potential ideological biases of scholars allows us to more accurately compare their views. This would make data collected by TRIP and other groups far more valuable. If we can evaluate issues with an understanding of the role of ideology, we will benefit from the vast knowledge and experience of international relations scholars.

Aidan Donovan is a junior at the College of William and Mary, majoring in Economics and Government. He has worked as a Research Assistant for TRIP since February of 2019. His interests include law and economic policy, and he is particularly interested in understanding how scholars think and communicate with policymakers and the public.